Why We’re Still Obsessed With Watergate

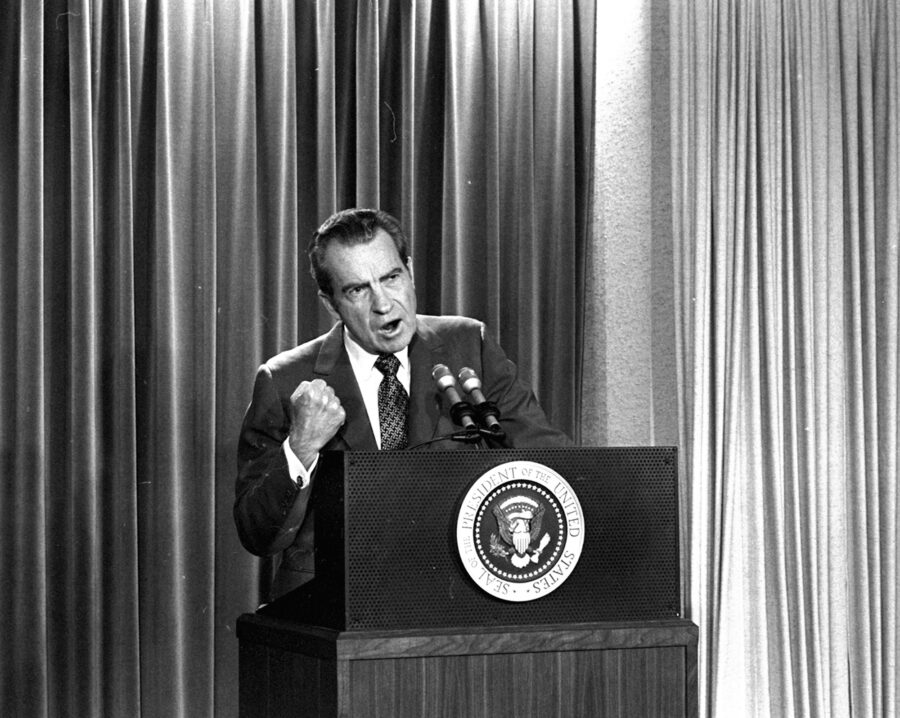

As we commemorate, on its 50th anniversary, the Watergate crisis that brought down Richard Nixon’s presidency, it is worth remarking on the extraordinary fact that we’re still commemorating it at all.

Presidential scandals, after all, don’t age well. Few people can tell you much if anything about the Whiskey Ring that tarred Ulysses Grant’s presidency, the corruption flaps that rocked Harry Truman’s and Dwight Eisenhower’s White Houses, or even the Teapot Dome affair, which stood as the benchmark for presidential malfeasance until Nixon came along a half-century later. Even controversies of recent vintage that seemed like a very big deal at the time — Iran-contra, the Lewinsky affair, George Bush Sr.’s Christmas Eve pardons, George Bush Jr.’s U.S. attorneys scandal — didn’t occasion national reflection on their fifth or 10th or 25th anniversaries on anything like the scale that Watergate did.

One wouldn’t necessarily have predicted this. For a time, in the 1980s especially, journalists became enamored of a narrative that imagined Nixon staging a “comeback” or “rehabilitating” himself, as the overstocked smorgasbord of presidential crimes — the Kissinger wiretaps and the White House tapes, the illegal break-ins and the FBI, CIA, and IRS abuses, the hush money and the serial lying — receded into history. Newsweek put Nixon on its cover, declaring, “He’s Back”; pundits whom he wined and dined gushed about his command of world affairs. One historian ventured the colossally mistaken judgment that Watergate was destined to become a “dim and distant curiosity.”

But Watergate never faded. Younger generations, it’s true, may no longer get references to the Rosemary Stretch, puns about Hugh Sloan and the Hughes Loan, or allusions to the Prussian Guard. But we still talk about political smoking guns; the Enemies List and the Saturday Night Massacre remain reference points in our political cultures; and we continue to name new scandals with the suffix “-gate.” Watergate has remained the scandal by which subsequent ones are measured. Textbooks and high school teachers still explain it as the defining event of the Nixon years — and, indeed, a watershed in American public life that put an end to our heroic view of the presidency.

Why? How come Watergate stands the test of time, still provokes interest, still leads us every five or 10 years to look at it anew? One way to answer the question is to think of Watergate as a classic novel — and like many great novels, it has a gripping plot, larger-than-life characters, and a timeless theme.

As stories, scandals are notoriously difficult for the public to follow. There are no great books or movies about the Iran-Contra scandal. Whitewater lost its audience soon after it began. While the Lewinsky affair, as a sex scandal, generated its share of prurient interest, the story was too simple and tawdry to become the stuff of high drama. Teapot Dome and other pre-Watergate scandals mostly dealt with straightforward venality.

But Watergate could have been scripted by Hollywood.

Act One was Nixon’s steady descent into ever-greater criminal wrongdoing. Starting with his and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger’s decision in early 1969 to secretly wiretap journalists and spy on their own staff to find out the source of leaks about Vietnam, Nixon grew increasingly comfortable with abusing the power of the presidency to punish enemies, shore up his own power and pursue his paranoid fantasies. There was the drafting of the so-called Huston Plan in 1970 to carry out political intelligence from the White House; the installation of the secret taping system in 1971; the creation of the Plumbers Unit that began committing illegal break-ins; and of course the burglaries at the Watergate complex itself, where the Democratic Party had its national headquarters.

But if Nixon’s steady arrogation of power early in his presidency appears in retrospect as a disaster in the making, most of his criminal behavior remained unknown to the public at the time. It is Act Two of Watergate — the unraveling — that made the saga riveting day to day and that still gives the story its propulsive excitement. June 17, 1972 was not the start of the Watergate narrative but its hinge: The arrest of the burglars that day led a few reporters to start digging into what they were doing and who they were working for. Those early revelations in turn spurred the Senate to convene an investigatory hearing led by North Carolina’s Sam Ervin, which became an unlikely television blockbuster. Their jaw-dropping discoveries — about Nixon’s taping system, his ancillary abuses of executive power, and above all the sweeping White House cover-up operation — then led to the appointment of a special prosecutor, whose firing that fall made impeachment a realistic prospect for the first time in a century. When a unanimous Supreme Court the following June made Nixon surrender tapes that incriminated him, America experienced the first and only presidential resignation in its history.

These surreal twists and turns, these unprecedented shocks and surprises, kept Americans engaged and enthralled in real time. So did a dramatis personae out of Damon Runyon: the crazed G. Gordon Liddy, with his creepy fondness for tools of German manufacture; the thuggish Chuck Colson, who said he would run over his grandmother to help Nixon ; the nerdy John Dean, White House counsel at the precocious age of 32, whose steel-trap memory made his implication of Nixon in the cover-up seem suddenly credible; and dozens of others in parts large and small. Above all, Nixon, at the center of it all, boasted a psychological profile of unfathomable depths — a subject of brooding anger and gnawing resentments that he struggled to submerge in his striving for acceptance and power. Secretive and inscrutable, he was the president who launched a thousand psychohistories, who ultimately assumed his place as the archetypal political villain of the modern age.

Nixon may be the rare political subject who never ceases to be interesting, but even he would not captivate us anew every five or 10 years had not Watergate tapped into something deep in the American psyche. The United States was fractured and divided in the early 1970s, in some ways as divided as we are today, but Nixon managed to bring about, however temporarily, a strange and rapid consensus. As the evidence mounted, Republicans and Democrats, right-wingers and left-wingers, converged around the imperative that he must resign or be removed from office. Across the spectrum people saw that at the root of Watergate was Nixon’s heedlessness toward the legal and constitutional limits on his power, his belief, as he later told the British television personality, “that if the president does it, that means it’s not illegal.” Nixon treated the FBI, the CIA and the IRS as instruments of his own will and desire. Burglaries and perjury did not trouble him.

This view of limitless executive power alarmed Americans — and still compels our attention — because it taps into the most fundamental concerns in American politics since its founding: the fear of the subversion of democracy by an overly powerful executive. The American Revolution may have begun as simply a war for independence from Britain but it came to embrace the rejection of monarchy itself. So fearful did the Americans remain of centralized power that their first government, the Articles of Confederation, allowed for no executive at all. And while the Constitution of course established a presidency, its powers were carefully hedged. Thereafter, whenever any president sought to expand those powers — Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt — he was decried as a would-be monarch, tyrant or dictator, with the terminology changing according to the era.

Typically, after a moment of controversy passes, we come to see these sorts of attacks on a president as partisan, hyperbolic, even hysterical. (Remember the panic about Barack Obama’s supposedly dangerous appointment of executive branch “czars”?) But with Nixon they were well-founded. They came, moreover, after several decades of an increasingly “imperial presidency”,” as the phrase had it: an executive branch that was growing in size, scope and power, through World War II and the Cold War, consigning the (relatively) weak presidency of the 19th century irretrievably to the dust heap of history. Watergate was a real and necessary reckoning with the growth of presidential power and the dangers that it posed.

Watergate, of course, had a happy ending. As the newspaper columnist Jimmy Breslin cheekily put it in the title of his book, “The Good Guys Finally Won.” That fortuitous outcome has allowed Americans to tell and retell the tale of Watergate over the years with detachment, relief, even optimism. We take comfort in knowing that a threat was repulsed and democracy protected. Today, as we fight our way through another reckoning with presidential abuse of power on a grand scale, unable to know how it all ends, the saga of Nixon’s downfall at the hands of the press, the courts, the Congress and public opinion — all united, despite political differences, to rein in a criminal presidency — becomes, rather unexpectedly, more comforting than ever.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO