What a Roberts compromise on abortion could look like

When the two sides in the abortion debate squared off at the Supreme Court last fall, they agreed on one thing: There was no middle ground.

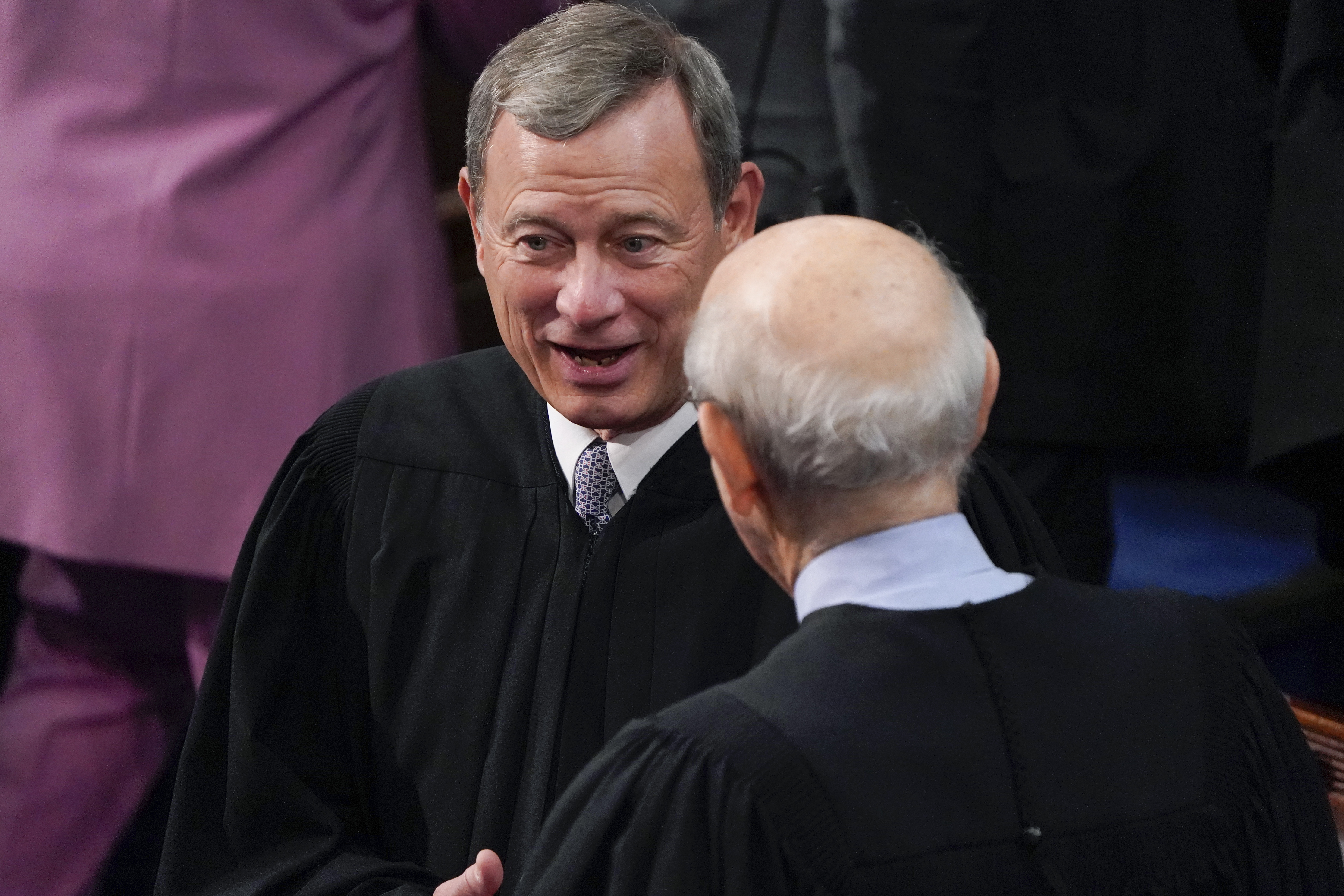

Now, any hope abortion rights supporters have of avoiding a historic loss before the court lies with Chief Justice John Roberts crafting an unlikely compromise. In the wake of POLITICO’s report last month on a draft majority opinion that would overturn Roe v. Wade, Roberts would have to convince at least one of his five Republican-appointed colleagues to sign on to a compromise ruling that would preserve a federal constitutional right to abortion in some form while giving states even more power to restrict that right.

Can Roberts thread that needle and how would he do it?

The Supreme Court has been very tight-lipped since the leak of the Roe opinion draft, and the court never comments on opinions ahead of time. But a deep dive into Roberts public speeches and commentary at court arguments may offer somewhat of a roadmap to what a Roberts compromise might be on Roe if he is able to find one at the 11th hour. The court could issue its abortion ruling any time in the next two weeks, before the justices leave town for their usual summer break.

The central organizing principle for a Roberts opinion is likely to be one he has articulated many times: that the court shouldn’t issue a sweeping decision when a more modest one would do.

“I think judicial decisions should be narrower, rather than broader,” Roberts said at the University of Minnesota Law School in 2018. “Courts sometimes get in trouble when they try to sweep more broadly than necessary.”

In the abortion case currently before the court, lawyers for the state of Mississippi are asking the justices to uphold a law that would ban most abortions after the fetus has reached 15 weeks. That was, indeed, the state’s main ask in July 2020, when Mississippi officials petitioned the court to take the case.

However, by the time the state filed its opening brief a year later, the court had shifted further to the right with conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett replacing the late liberal icon Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Mississippi shifted its sights accordingly and told the high court that it was time to wipe out the landmark 1973 decision establishing a federal constitutional right to abortion, Roe v. Wade, and a 1992 ruling that largely preserved that right, Casey v. Planned Parenthood.

“This Court should overrule Roe and Casey,” Mississippi’s brief said, mounting a headlong attack on those critical precedents. “Those precedents are grievously wrong, unworkable, damaging, and outmoded.”

At arguments in the case last December in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Mississippi Solicitor General Scott Stewart urged the high court to “just go all the way and overrule Roe and Casey.”

Despite the sharply conservative lean of the new court, abortion rights advocates mounted the flipside of that argument and sought to defend Roe and Casey from the frontal assault while making no concessions. Upholding the statute would amount to “gutting Casey and Roe,” the brief for the Jackson, Miss. Clinic that challenged the law said.

However, during the arguments, Roberts seemed to stake out a middle ground. He suggested that the essential right to end a pregnancy could be maintained even if states were allowed to sharply limit abortion before viability outside the womb, which is generally considered to be around 22 or 23 weeks.

The chief justice indicated that the pivotal issue for abortion rights may be whether a pregnant person has sufficient opportunity to get an abortion, not the age of the fetus.

“There is a point at which they’ve had the fair choice — opportunity to choice,” Roberts said, seeming to deliberately adopt the language of abortion rights advocates.

“Why would 15 weeks be an inappropriate line?” the chief justice asked. “Because viability, it seems to me, doesn’t have anything to do with choice. But, if it really is an issue about choice, why is 15 weeks not enough time?”

When Roberts floated that idea, advocates for both sides urged him not to adopt a centrist position leaving the abortion right on the books but focusing more on whether those who become pregnant have a genuine chance to seek an abortion.

“A ‘reasonable possibility’ standard would be completely unworkable for the courts,” said Julie Rikelman of the Center for Reproductive Rights, who argued for the abortion clinic challenging Mississippi’s law. “It would be both less principled and less workable than viability.”

Rikelman then offered a slippery slope argument, that a line drawn at weeks by the law at issue would quickly slip away.

“Without viability, there will be no stopping point. States will rush to ban abortion at virtually any point in pregnancy,” she told Roberts. “Mississippi itself has a six-week ban that it’s defending with very similar arguments as it’s using to defend the 15-week ban.”

As a technical matter, the state did not completely reject the position Roberts appeared to be advancing at oral argument. While Stewart threw cold water on such an approach at that session, the state’s brief seemed to leave the door open to such a result by contending that the court should “at least” drop the viability distinction even if it doesn’t gut Roe completely.

However, Stewart emphatically warned against an approach built on access or opportunity to get an abortion.

“It’s a very hard standard to apply. It’s not objective,” he said. “You couldn’t say necessarily for certain that a certain number of weeks one place would be an undue burden but would be okay another place.”

Still, not everyone thinks the approach Roberts floated would be completely unprincipled or unworkable.

A conservative veteran of Supreme Court confirmation battles, Curt Levey, said he thinks the approach of upholding the 15-week ban and leaving other issues to other cases is entirely consistent with Roberts’ stated philosophy.

“If ruling narrowly means anything, it means not going beyond what you need to decide a case,” said Levey, executive director of the FreedomWorks Foundation. He said he found Roberts’ rationale for upholding the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate far more perplexing and contorted than the abortion-rights stance he seemed to advocate last December.

“I’m used to Roberts being unprincipled [but] here, it was perfectly plausible,” Levey added. “I’m not going to lie and say I don’t think the cleaner thing would just be to overturn it, but he certainly didn’t get me angry.”

Some scholars note that there’s an obvious precedent for a Supreme Court opinion that purports to preserve the basic right to an abortion while allowing further intrusions on that right. That’s exactly what happened in 1992, when many expected the demise of Roe. Instead, a highly unusual three-justice joint opinion in Casey dropped Roe’s trimester-based framework for abortion restrictions, switched to a standard involving when a fetus was viable and instructed courts to look at whether limits passed by states created an “undue burden” on those seeking abortions. None of those three justices — Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy and David Souter — remain on the court.

“It dramatically changed the preexisting legal doctrine without overruling what the controlling opinion called the essential holding of Roe v. Wade,” said Indiana University law professor Daniel Conkle. “Yes, it takes some judicial creativity, you might say, but it would not be difficult to imagine Chief Justice Roberts writing an opinion of a somewhat similar nature.”

However, Conkle noted that the court’s abortion decisions tend to get extraordinarily intensive attention from lawyers, scholars and the public, meaning a mushy opinion is likely to come under swift attack.

“The proof is in the pudding to some extent of whether Roberts writes an opinion that can withstand that sort of scrutiny,” the professor added.

Roberts’ comments during the arguments last December weren’t the only sign he might be more inclined than his conservative colleagues to back away from the brink from overturning Roe.

Two years ago, Roberts sided with the court’s liberal wing to block a Louisiana law that could have forced all but one of the state’s abortion clinics to close. He said the measure was virtually identical to a Texas law which the Supreme Court’s liberals and Kennedy voted to block in 2016.

Roberts voted to let the Texas law take effect, but he said that once the court ruled that measure was too burdensome, the court shouldn’t rule the other way in Louisiana just because Kennedy left the court and was replaced by Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

An opinion that upholds Mississippi’s 15-week ban but claims to leave Roe in place might also save the court from being the focus of a hot summer of protests over abortion. Keeping the court out of the political spotlight whenever possible has also been another of Roberts’ goals, noted Cardozo law professor Kate Shaw.

“I think that would have, from Roberts’ perspective, the advantage of slowly acclimating the country to the erosion of abortion rights and could potentially dull the outrage and response,” said Shaw, who was a law clerk to Justice John Paul Stevens. “It’s absolutely the Roberts playbook. … From Roberts’ perspective, it could be a kind of P.R. boon to the court.”

However, Shaw believes Roberts’ efforts might achieve so little delay that he or others could conclude it simply isn’t worth it.

“All that would do is defer issuance of that Dobbs draft for like one year,” she said. “All it would do is slow the inevitable.”

Of course, the current ideological math on the Supreme Court means Roberts’ views could wind up as little more than a historical footnote unless he can persuade one of his Republican-appointed colleagues to join him in an arguably more centrist approach on abortion, for as long as that might last.

“It doesn’t seem to me inconceivable that he could convince Kavanaugh to join in that opinion,” Shaw said.

While any ruling from Roberts ostensibly preserving Roe might temper the overall reaction to the court’s looming abortion decision, it would be viewed by many conservatives as just the latest betrayal of their movement and principles by the chief, who unexpectedly emerged as a swing justice on the court in a handful of major cases over the past decade. His decision in 2012 to join the court’s liberals and uphold the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate profoundly disappointed many activists on the right who were expecting Roberts to help deliver a crippling blow to Obamacare.

Roberts also joined a 6-3 decision in 2015 that allowed Obamacare’s insurance subsidies to keep flowing nationwide — a ruling Justice Antonin Scalia dismissed as “pure applesauce.”

Since then, Roberts provided the critical vote to block President Donald Trump’s efforts to repeal deportation protections and other benefits for so-called Dreamers. The chief also sided with liberals to hold off a major challenge to government agencies’ regulatory powers and even wrote for the majority in a 5-4 decision rejecting the Trump administration’s efforts to add a question about citizenship to the 2020 census.

To be sure, there are many other decisions — most, in fact — where Roberts aligned with his conservative colleagues on issues such as voting rights, campaign finance and the death penalty.

The finer points of Roberts’ views on abortion rights could end up being mere idiosyncrasy, since many abortion rights advocates believe Roberts won’t get any takers for whatever opinion he may be drafting.

Attorney Kathryn Kolbert, who argued at the high court for the abortion rights side in Casey three decades ago, predicted on a recent Scotusblog podcast that she sees no way Roberts diverts his colleagues from their increasingly intense desire to overturn Roe.

“Not a chance in hell,” she said bluntly.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO