Opinion | The Emptiness of Democrats’ Big Deal

If the San Francisco 49ers are looking for a place-kicker, they might want to look across the continent to the House floor, where Speaker Nancy Pelosi has just booted Democrats’ increasingly bitter infrastructure-budget dispute several weeks down the legislative road. The agreement adopted Tuesday after some painful late-night diplomacy is a masterpiece of legislative prestidigitation: a $3.5 trillion budget bill that is “deemed to have passed,” but with not a dollar actually approved for anything yet; and a promise of a House vote next month on the bipartisan infrastructure bill with no guarantee the party will actually come together to vote for it.

Normally, any deal that grips Congress like this comes with a big win for someone — the party in power claims a “W,” and representatives go back home and brag about the bacon they brought home.

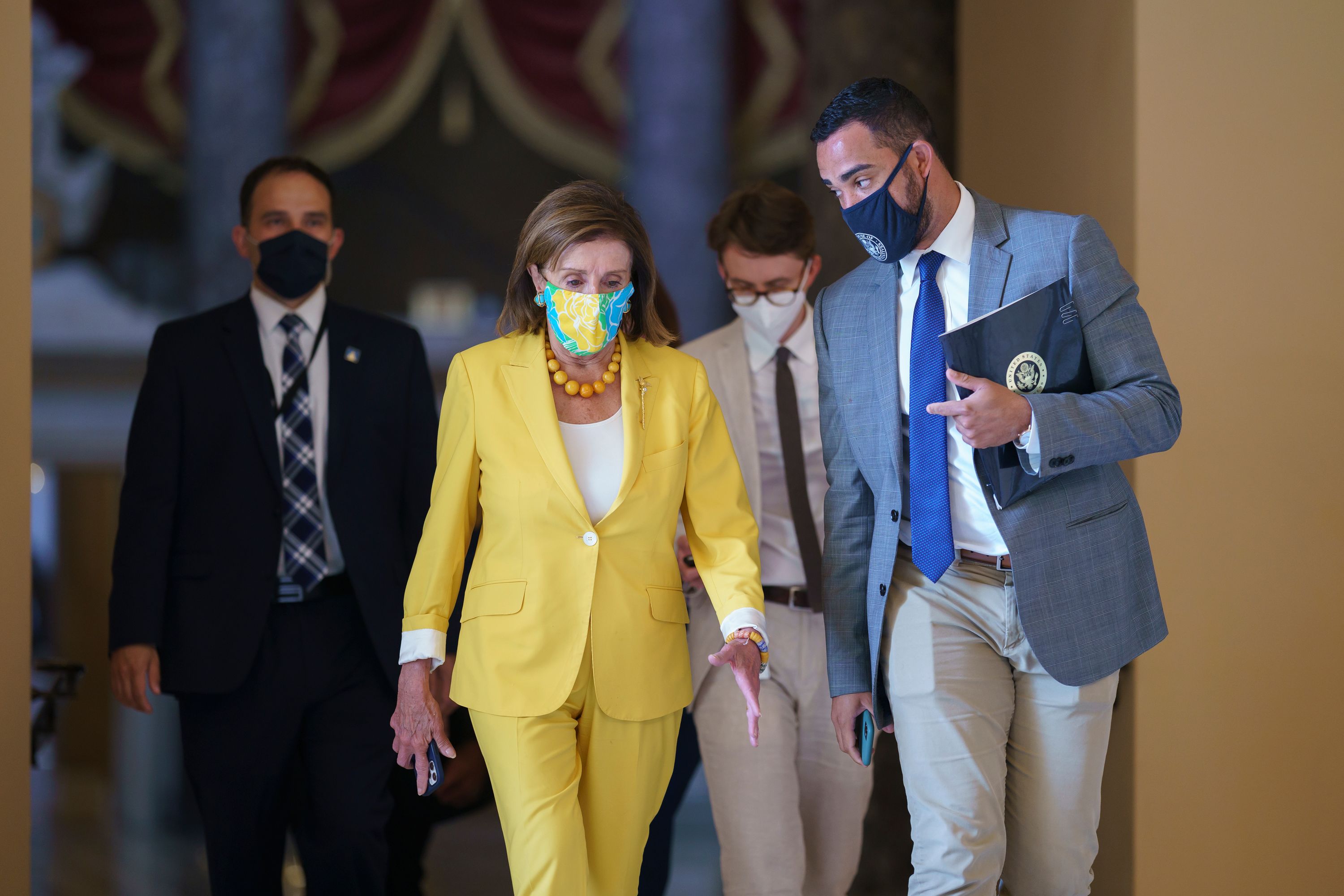

Not this one. Pelosi managed to keep her party from falling apart at a crucial moment, and that’s about all. Moderates still can’t point to passage of the bipartisan infrastructure bill, and progressives are angry that they’ve lost leverage to pass a sprawling social spending package.

The agreement has to be accorded some level of respect, since it keeps alive the possibility of victory for President Joe Biden’s agenda. But what it really shows, besides Pelosi’s deftness, is just how far Democrats are from a coherent governing force. Particularly with a huge trust deficit between the party’s factions, the struggle between the left and center could still derail Democrats’ best shot at a set of accomplishments to buoy them in 2022 and beyond.

If we step back from the legislative skirmishes of the past week, we can see that the roots of the Democratic divide go back to last November, to the arguments over what happened, and to the way to respond to those results. In those first days after Election Day, Democrats discovered that their hopes for widespread gains were dashed: Instead of gaining 10 or 5 House seats, they wound up losing 13, leaving a House majority you could count on the fingers of one hand. Their control of the Senate came down to a Georgia Senate race where Republican David Perdue came within a quarter of one per cent of avoiding a runoff. (Their hopes for gains at the state level were equally crushed; they did not win control of a single chamber anywhere in the country.)

In the wake of these results, different factions of the party took two very different lessons. For the more centrist Democrats like Virginia Rep. Abigail Spanberger, who barely survived, she and others in competitive districts complained that they had been hurt badly by both cultural (“defund the police!”) and economic (“socialism!”) charges, leading to defections from traditional Democratic voters. For more progressive (and self-defined socialists) like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the turnout of Black, brown and left-leaning voters was the key to Biden’s victory; the failures in the more purple districts were due to a lack of clear and compelling messaging.

The more consequential question, however, was what to do in the face of perilously narrow Democratic margins. Both factions of the party saw the same daunting challenge: the likely prospect of the loss of the House in 2022 (history and redistricting seemed to guarantee that), and the need to offer the country demonstrable proof that Democrats could deliver tangible results. But what kind of results?

The bipartisan infrastructure bill was one answer: a $1.2 trillion package — with some $579 billion of new money — to fix the roads, bridges, rails, grid and broadband across the country. It would be a rare example that Biden and the Democrats were serious about reaching across the aisle and making things better.

The president and congressional leadership chose that path, but also something much more ambitious — even unprecedented — a multitrillion-dollar plan that would expand Medicare and child care and provide free community college, universal pre-K and a legion of other initiatives. It would move the United States several steps closer to the kind of social safety net common in most of the industrialized world. And it would do so in a political environment unlike anything in the past.

Historically, major social legislation has always followed sweeping Democratic victories in the political arena. The New Deal and the Great Society legislation came after Democrats won both presidential landslides and massive congressional majorities (and-not-so-incidentally — significant numbers of Republican allies). We’ve never seen an effort to enact such sweeping changes on the domestic front with so little breathing room.

Further, more centrist Democrats might have pointed to Biden’s election as an argument for more caution: he’d swept to victory despite — or perhaps because of — his stances on immigration, Medicare, and bipartisanship. In another time, it might well have been Biden, Pelosi, and Schumer cautioning against overreach, and fighting to keep a small group of progressives inside the tent.

But something very different happened. For one thing, the pandemic’s impact on the economy made once-unimaginable spending ($1.9 trillion on Covid relief) a rational, widely approved response to joblessness and closed businesses. For another, the pandemic revealed a level of inequality that made the idea of taxing the wealthy at higher rates a broadly popular notion: a notion that fit well with the more populist economic beliefs of a majority of congressional Democrats.

Finally, and perhaps more important, the very prospect of losing the House (and possibly the Senate) next year has fueled the hunger of Democrats for a highly ambitious set of social programs. If we only have a year so in power, the argument goes, let’s use that power as much as we can, the way we didn’t back in 2009. And maybe it will wind up giving us a case for 2022. The same $3.5 trillion goal that centrists see as politically unappealing in their districts is seen by most in the caucus as their best chance to stay in the majority. And there is a sneaking suspicion among some on the left that if the moderates had their druthers, they’d just as soon pass the infrastructure bill and say: “enough!” (The revolt by a handful of moderates in recent days is certainly not going to put those suspicions to rest.)

For Biden, Pelosi and Schumer, there remains one pesky problem in embracing a massive budget reconciliation package: they do not yet have the votes for anything like a $3.5 trillion bill. We don’t know what price tag Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema, Josh Gottheimer and other centrist Democrats will find acceptable. We don’t know if House progressives will doom the infrastructure bill if the final Senate figure on the reconciliation package is unsatisfactory. We don’t know if a sliver of moderates will indeed tank the social safety net bill once infrastructure passes, in the belief that they cannot win in their districts if the cost is too high.

But give the Democrats credit on one front: if passing these bills was an Olympic event, it would come with the highest “degree of difficulty” rating in history.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO