Opinion | When Black Men Meet White Communities

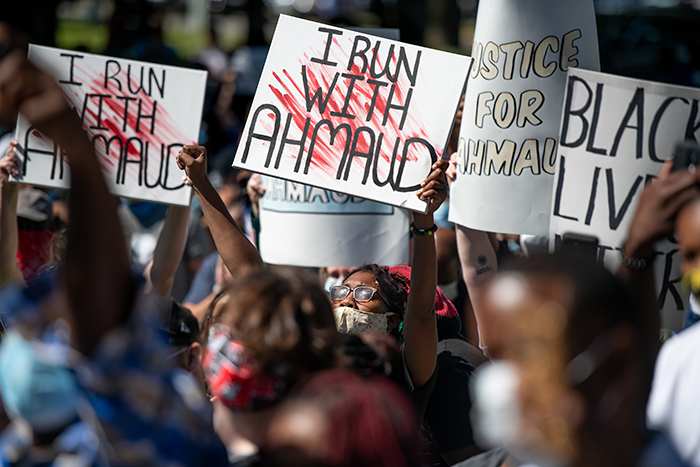

Ahmaud Arbery’s killers were convicted of murder for what many — including Emmett Till’s cousin — called a “modern-day lynching.” Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man with ambitions of becoming an electrician, was chased by three white men in pickup trucks. White men in pickup trucks armed with shotguns. Tragically, Arbery, who was unarmed, did not survive their encounter.

The murderers — Travis McMichael; his father, Greg; and their neighbor, William “Roddie” Bryan — said they believed Arbery was the supect behind a string of burglaries in their suburban Georgia neighborhood. So, they said, they were attempting a citizen’s arrest, a practice dating back to Medieval England, with particularly rancid ties to slavery in the U.S. (Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law was repealed earlier this year in response to the killing.) But video evidence showed the one-time high school football player’s only crime was being Black at the wrong place and time. And for that, he was hunted and killed.

This incident highlights the legacy of “sundown towns,” when Black people caught in the “wrong” neighborhood or on the “wrong” street could face a beating, the burning of a cross in one’s yard — or an outright lynching.

Of course, the “wrong” neighborhoods and streets are those that are predominately white, many of whose denizens aim to maintain an exclusively white community. Some people who live in these neighborhoods want their schools, restaurants, business owners, delivery people — and politicians — to all be white. They also want the criminal justice system to maintain a white dominance in everything from who holds the gavel on the judge’s bench to who sits in the jury box.

This is why the Arbery killing is such a throwback; it’s an example of classic racism baked into social institutions. Citizen’s arrest laws, and the criminal justice system in a corresponding fashion, perpetuate and sanction the protection of white communities from people who look like Arbery. These laws let people zero in on perceptions of criminalization, and then subsequently use self-defense laws, such as “stand your ground,” as justification for their use of force.

My research has focused on the experiences of Black men in predominantly white communities and their experiences with law enforcement and the criminal justice system. In a quantitative and qualitative study, I found that middle-class Black men were significantly less likely than others to exercise in predominantly white neighborhoods. That means they’re much less likely to take a jog through their own streets. Why? Their blackness becomes weaponized. Even when they’re unarmed and aren’t committing any crime, they’re perceived as a threat — and that subsequently justifies surveillance and use of force.

In situations similar to the killing of Ahmaud, white people are over eight times more likely to be found not guilty when claiming self-defense if the victim is Black, compared to when the victim is not Black. These killings speak to a key social psychological concept: subjective uncertainty, which states that when there is minimal information, people rely on stereotypes to discriminate. In the case of Ahmaud, that discrimination resulted in homicide.

The consequences of subjective uncertainty are not limited to killings. Rather, there is a trickle-down effect of the criminalization of Black lives. It carries over to Black people having police called on them. It allows people to treat them as suspects and pursue them in virtually every quotidian aspect of their lives: while traveling, exercising, delivering packages for companies like Amazon and viewing a new home or business property. My research highlights how criminalization impacts Black people’s mental and physical health, job pursuits — and their ability to build wealth.

In the killing of Arbery, the criminal justice system was originally operating as designed. Every step of the prosecutorial process seemed to foretell the likelihood that the McMichaels and Bryan would be exonerated.

First, the district attorney’s office initially advised the police not to make any arrests. (A former district attorney is facing charges for her role in the Arbery case.) Second, the jury had a skewed racial composition relative to the area (11 white people and one Black person in a county that is roughly 30 percent Black). Third, one defense attorney tried, unsuccessfully, to ban Black pastors from the courtroom, painting them as a menacing presence — another attempt to police Black people in a public space.

Apparently, the mere presence of Revs. Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson sitting quietly in the courtroom posed a threat, similar to how Ahmaud’s mere presence in Satilla Shores posed a threat.

Travis McMichael, who ultimately shot Arbery, testified that he just wanted to talk to him and make a citizen’s arrest. Black people know instinctively that “we just wanted to talk to him” is code for “we wanted to put him in his place.”

Collectively, these narratives are straight out of the hunter’s playbook, dating back to the slave-catcher origins of American policing and the founding of the Ku Klux Klan. These narratives are used to justify the treatment of Black people and prevent them from truly experiencing freedom as guaranteed under the Constitution. (And, in fact, Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law was originally used to catch enslaved people fleeing bondage.)

Those narratives can play out in eyebrow-raising ways, such as when one defense attorney described Arbery’s toenails as “long” and “dirty,” eliciting gasps inside the courtroom and outrage outside it.

This is at the heart of it. It is not what Arbery was doing. It is about who he was, what he looked like — his chocolate skin being the biggest threat of all. Black people in white communities pose danger. That’s a narrative we’ve seen play out in pop culture, such as in the classic film “The Birth of a Nation,” which depicted Black people as simpletons in Congress picking their toenails and as as violent brutes attempting to rape innocent white women. In the film, the KKK saves the day from Black people and Blackness as an ideology. Though many people might not wear white hoods anymore, at least publicly, the ideology of the KKK is baked into some local communities and puts a chilling effect on objectivity within the criminal justice system.

But despite all of these classic racist tropes trotted out in the courtroom, the outcome of this trial was different. Why? First, video is powerful. The jury watched the video of the murder at least three times at the end of the trial. Without the video, which Bryan filmed and later released, most people would not know about the killing of Arbery. The system would have operated as designed. There may not even have been any charges in this case.

Second, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation was called in to oversee the case. My research on policing suggests this additional oversight at the state or federal levels helps create more transparency, objectivity and accountability for criminal proceedings. This oversight model was used in the Derek Chauvin trial for the murder of George Floyd. Another example of successful oversight: In Georgia, the Republican-led Legislature voted to repeal its 1863 citizen’s arrest law. Given the history of these laws, other states should follow suit.

Collectively, the conviction of these three men, and the jurors who made this decision, suggests things may be changing for the better. Self-defense of whiteness may no longer hold sway in our courtrooms. But, then again, there’s 18-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse whose self-defense claims resulted in his acquittal. (Though Rittenhouse killed two white men and injured a third, he shot them during a Black Lives Matter protest, infusing the shootings with distinctly racial overtones.)

So, while many are rejoicing that “the spirit of Ahmaud defeated the lynch mob,” as attorney Ben Crump said, we need to continue working together to ensure that those who perpetuate unjustified acts of vigilantism are held accountable as well.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO