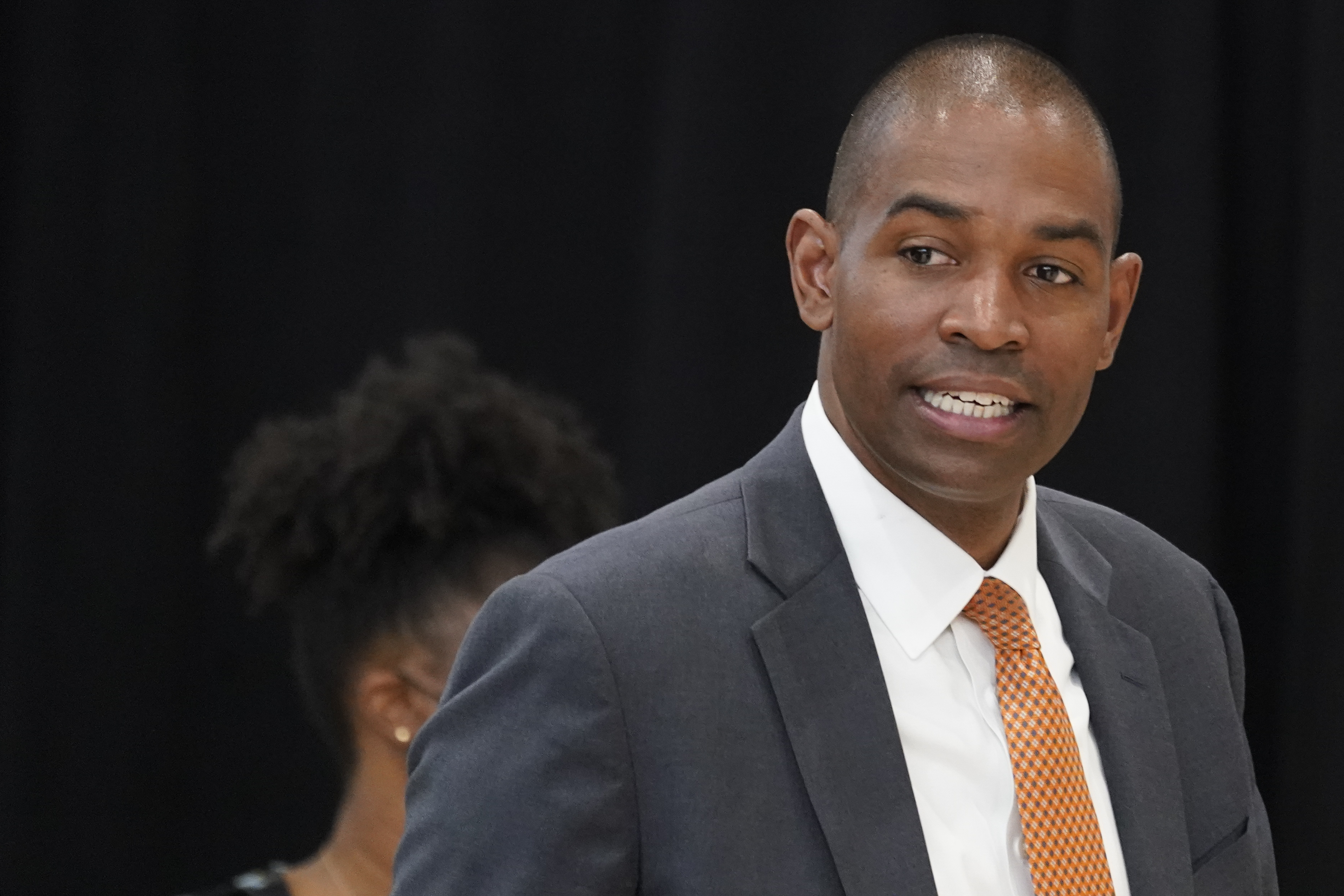

Delgado quit Congress to be Hochul’s No. 2. Now he actually needs to win.

ALBANY, N.Y. — Lt. Gov. Antonio Delgado’s experience winning competitive elections rivals that of any of the 62 people who have ever been elected lieutenant governor in New York.

The former Democratic congressman from the Hudson Valley shows comfort on the campaign trail and can win over crowds with a quick smile. He has the advantage of incumbency, the backing of the Democratic establishment, and he might have 20 times as much campaign cash as his two competitors.

But it’s far from certain that he’s the definitive front runner in the June 28 primary after leaving Washington to serve as second-in-command in state government.

“This is a race with question marks and not exclamation points,” said Democratic consultant Bruce Gyory, who has served as an adviser to several New York governors.

The role of lieutenant governor has also always been important because it’s first in the line of succession and has been amplified in recent years during scandals in Albany: when then- Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul succeeded Gov. Andrew Cuomo when he resigned last August and when David Paterson replaced Gov. Eliot Spitzer in 2008.

Even Delgado came into office last month after a scandal. Hochul picked him to replace Brian Benjamin, who was indicted on federal corruption charges just seven months into the job.

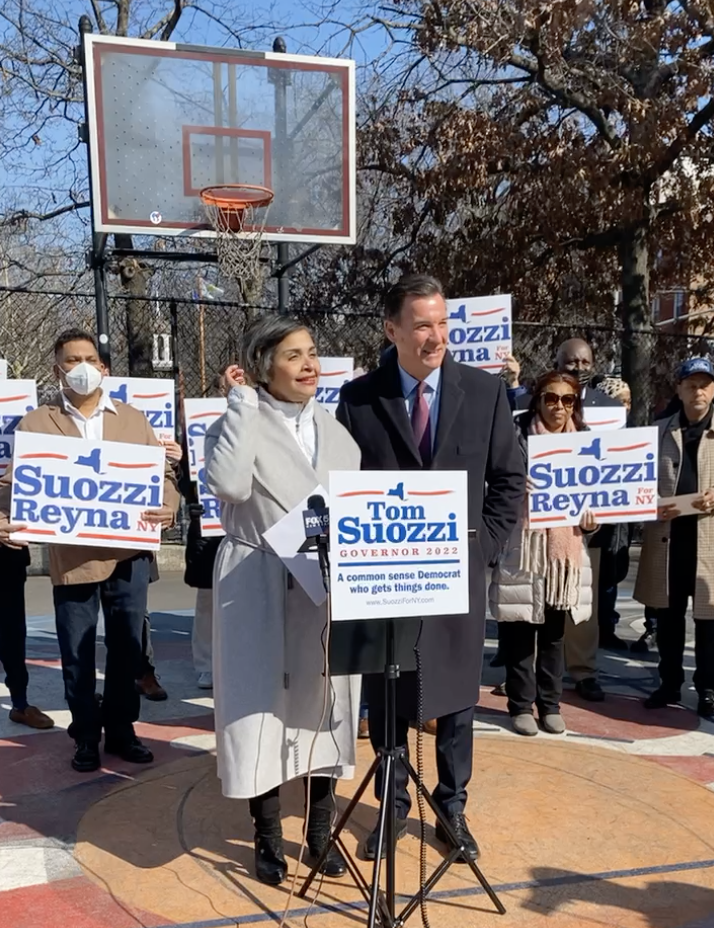

The former two-term congressman and lawyer will now appear on the primary ballot with progressive activist Ana Maria Archila (New York City Public Advocate Jumaane Williams’ running mate) and former New York City Council Member Diana Reyna (who is running alongside Rep. Tom Suozzi).

The outcome of the race will affect Hochul, who has emerged as the clear front runner in her own primary the same day. In New York, lieutenant governors run on their own in primaries but as a ticket with the governor in the general elections.

That means Hochul could be forced to run alongside a Democrat she did not pick, and one whose politics could make the general election more challenging — and life in office complicated.

If Delgado wins his primary and the two win as a ticket in November, Hochul will wind up with a dedicated ally for her causes for four years. Delgado said as much, even as his opponents called for more independence from the office holder.

“My job as a partner is to make sure that in our shared capacities — we bring to the table different outlooks different perspectives, different experiences — that we try our best to complement each other for the betterment of the state,” Delgado said in a brief interview. “That is our shared objective, that is our shared goal, and that is certainly my orientation to this role.”

Archila, who is backed by the Working Families Party and a host of progressive organizations, has a different view of the job.

“The lieutenant governor’s role is an elected role, but it’s used as if it were an appointed role by the governor, just as a surrogate,” Archila said in an interview in the early weeks of her campaign. “It could be an office that actually is used to make sure that the people who actually need government to work, the people whose lives are most at stake … that those folks actually have the ear of somebody in the executive branch.”

Electing the next lieutenant governor

If Archila wins — and she is considered Delgado’s closest competitor — there is little doubt she will spend much of the next four years commanding attention and use the office to critique Hochul whenever she doesn’t move aggressively enough on issues such as immigrant rights or housing that Archila has highlighted.

Past instances in which governors have had fallings out with their lieutenants have illustrated just how much of a headache a fraught relationship can be. Lieutenant governors have few specific powers other than presiding over state Senate sessions, but are usually relegated to touring the state on the governor’s behalf.

If the relationship turns truly bitter, the state constitution technically puts the lieutenant governor in charge if the governor leaves the state. So, theoretically, a governor stepping foot on New Jersey soil would instantly make Archila, if she wins, acting governor with the full power to do things like sign bills.

Clearly, the dynamic is a concern for Hochul, who spent much of her seven years as Cuomo’s lieutenant arguing that the office should be like that of a vice president: a prominent extension of the administration, with disputes kept behind closed doors.

Hochul’s effort to get her own lieutenant governor on the ballot required her to use significant political capital after Benjamin’s arrest: She got state lawmakers to change the law to allow her to do so.

Now, Delgado just has to win.

There’s not a lot indicating just how good the chances of this happening are in a race with no public polling. Observers are thus left looking at the lessons of past contests and how they might apply this year, and that can suggest plausible reasons to think that either Delgado or Archila could pull off a victory, as Reyna has not gathered the same type of support from grassroots groups or institutional power.

The most competitive Democratic lieutenant governor primary in recent New York history was the last one, when Hochul received a little over 53 percent of the vote in 2018 to beat Williams.

That’s the closest a progressive has come to toppling an incumbent Democrat in a statewide race in New York in decades. And it’s a small enough margin to suggest there’s a clear path for this to be the office that the left can flip.

Can a lefty progressive win?

Archila has notably built on the support received by progressives of the past.

Her long list of endorsers isn’t simply limited to officials and groups that could be expected to reflexively back the progressive Working Families Party-endorsed nominee. Several backers, such as Rep. Nydia Velásquez, the first Puerto Rican woman elected to Congress, are endorsing Hochul at the top of the ticket — but Archila for lieutenant governor.

“She’s secured the endorsement of every serious progressive organization in New York state as well as a cross-section of elected officials,” Assemblymember Phil Ramos (D-Suffolk), a supporter, said. He expects “the volume will be pumped up” from these endorsers in the coming days in a way that will help mitigate Delgado’s financial advantage.

Archila could also plausibly be helped by this year’s chaotic election calendar.

The usual rule of thumb in New York Democratic primaries in recent years has been that progressive insurgents tend to do better in races with lower turnout.

At the state level, the share of the registered Democrats that supports moderate candidates is larger than the share that supports progressive candidates. But there are often more progressive voters who feel passionately and are guaranteed to show up, meaning they can have an outsized share of the electorate in low-turnout contests.

It’s all about turnout

Early indications are that turnout for the June 28 vote might be low.

Courts have split the primary into two dates due to problems with the redistricting process, and that’s almost certainly going to decrease the number of people who will show up on either election day. The gubernatorial and lieutenant governor primaries are this month; the primaries for congressional and state Senate races are Aug. 23.

Recent trends, however, might be reversed and a lower-turnout contest could potentially help the establishment candidate this time around.

For example, the battle between Cuomo and actress Cynthia Nixon in the 2018 gubernatorial primary received more attention due to her star power than the Hochul-Williams-Suozzi fight that’s the marquee event on ballots this June.

Even people who obtained their information only from the national media or celebrity gossip magazines had some familiarity with the shape of the races four years ago. Some of those voters who learned to like Williams in the last contest because he ran alongside Nixon might have no familiarity with Archila this time around.

Insurgents in statewide races might also have been hurt by a 2019 decision to move gubernatorial primaries to June. In 2018, the Cuomo-Nixon primary was in September — which gave the candidates all summer to make their pitches.

This time around, the gap between the end of state legislative session in June and the statewide primary votes is measured in weeks. And some big pieces of those weeks have been dominated by coverage of events like Hochul signing bills on gun control and abortion.

The tighter time frame could help Delgado because he has millions of dollars to spend on the race: Voters might think about the race for the first time when they receive Delgado’s mailers or see his TV ads over the next week.

There are also several reasons to think that the math might be more advantageous for Delgado than it was for Hochul in 2018.

A major progressive stronghold in recent years is in what Gyory dubbed “Vermont West,” in communities along New York’s eastern border.

“From Peekskill south, all the way up to Plattsburgh, progressives have done well,” Gyory said. “Zephyr [Teachout] carried it against Cuomo [in 2014]; Nixon carried it against Cuomo; Bernie carried it against Hillary [in 2016].”

So if Archila wants to build on the gains made by people like Nixon, she’ll likely need to excel where former progressive candidates have done well. But here’s the rub: Delgado could perform best in parts of the Hudson Valley, much of which he represented in Congress. That would undermine Archila in a key region that progressive candidates typically count on for support.

Much of Williams’ strength in the 2018 lieutenant governor’s race against Hochul came from his ability to unite traditional progressive strongholds with neighborhoods in places that have large numbers of Black voters, like his home borough of Brooklyn.

A similar unification might be difficult for Archila.

A Colombian, she has shown signs of making new inroads among Latino leaders. But the number of Latino primary voters is usually about half the size as the number of Black primary voters, so a coupling of progressives with Latinos could place her far behind Williams’ total in 2018. And in a race with Reyna, a Dominican American, and Delgado, who identifies as Afro Latino, it’s far from a guarantee that she’ll be able to fully capture that vote.

So taken as a whole, the numbers for Archila could well wind up being difficult.

But there’s one major factor that could make the difference in the end. Archila has been campaigning since February, and her supporters have been laying the groundwork for a run like hers for longer than that. New York has not elected a Latino candidate statewide before.

Meanwhile, Delgado has only been campaigning since May, and his top supporters spent the months before that dealing with the fallout from the Benjamin scandal.

“Delgado should win,” Gyory estimated. “But, [due to] the lack of time, the Delgado campaign doesn’t have a large margin for error because Archila has been absolutely dogged and methodical in working the grassroots.”

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO