D.C.’s Enslavers Got Reparations. Freed People Got Nothing.

When we hear “emancipation” we think “Juneteenth” — the anniversary of June 19, 1865, when enslaved people in Texas, the last Confederate state with institutional slavery, received word they were free. But another important Emancipation Day took place in April 1862, 160 years ago and three years before Juneteenth, when Congress passed the law to free all the enslaved Black people in Washington, D.C.

Barely a year after the start of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln and Congress intended to set an antislavery example in the nation’s capital — a slave-holding city on the border of the slave-holding Confederate South. In 1849, as a young congressman from Illinois, Lincoln had already unsuccessfully proposed an emancipation plan for Washington D.C. Then, in 1861, as wartime president, he made a failed attempt to usher in emancipation in the border state of Delaware.

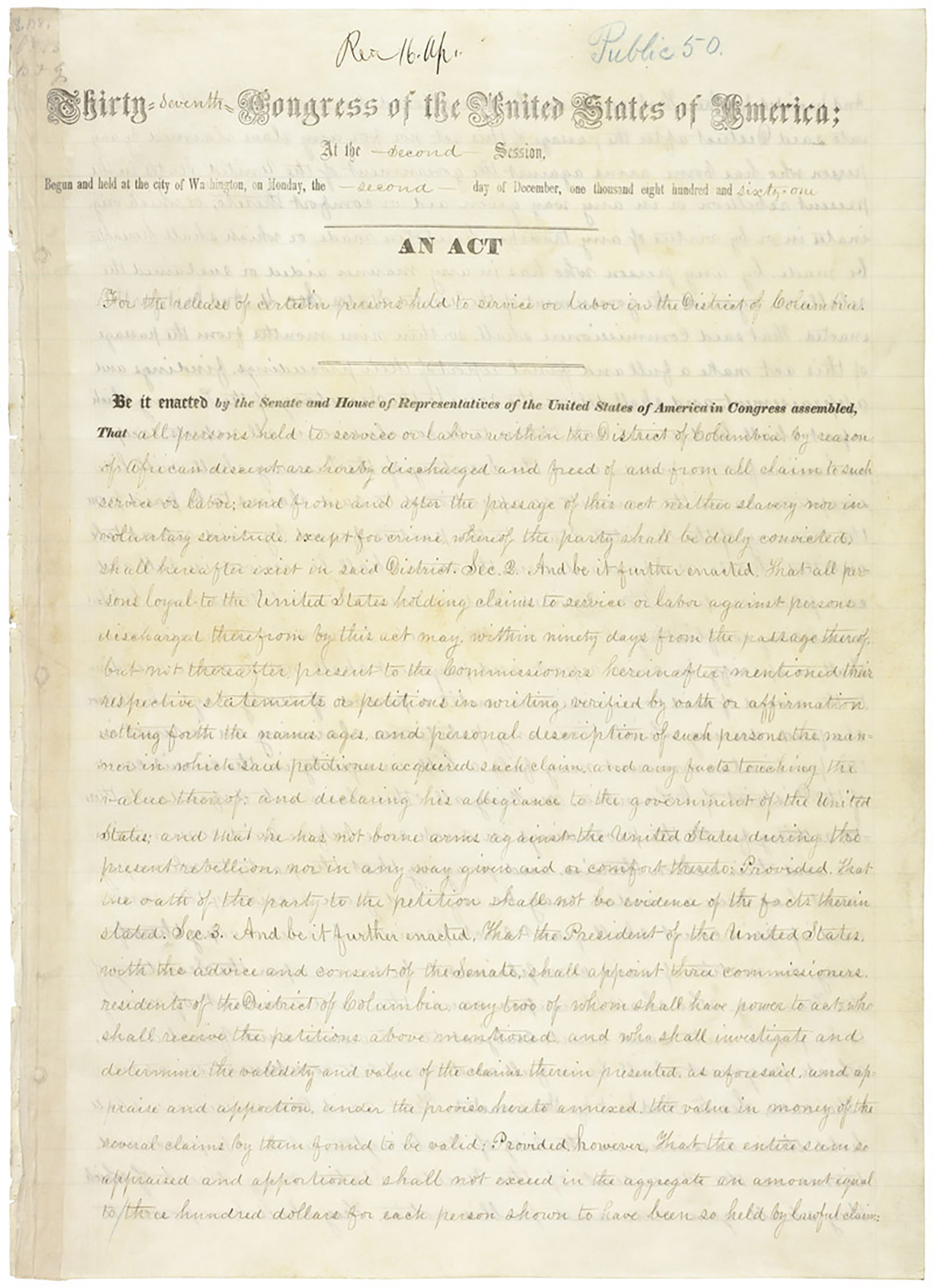

By spring 1862, Lincoln and members of Congress took decisive steps to enact the U.S. federal government’s first general emancipation of enslaved people in the only district, without a state legislature, where they had direct power to do so. Championed by Lincoln and Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, the proposal to end slavery in the nation’s capital was passed by decisive majorities in the House and Senate, before being signed into law by Lincoln on April 16.

In many ways, the District of Columbia Emancipation Act achieved in miniature what would later take place on an epic national scale during the great Emancipation that rolled across the Southern states from March to December 1865 — especially in its troubling execution, which would continue to hinder racial progress in decades and centuries to come.

In particular, in Washington, D.C., as in every single emancipation process that occurred in the Western world from Pennsylvania in the 1780s, to the U.S. South in the 1860s, to Brazil in the 1880s, former enslavers were seen as the aggrieved party. In D.C.’s emancipation, enslavers were paid significant compensation for their “lost property” in enslaved African-American people. The freed Black people not only received no reparations, but also experienced ongoing governmental neglect and exclusions. This racist process of emancipation led to policy choices that would ensure that the disadvantages of slavery would continue to be passed down, not ended, after slavery’s end.

The District of Columbia Compensation Act, signed by Lincoln, allocated $1 million dollars from the U.S. Treasury to pay off enslavers. If calculated as a proportion of total federal expenditure, this would amount to a staggering $12 billion today. The act also appropriated $100,000 from the federal budget (about $1.2 billion today, if calculated as percentage of total federal spending) to promote the relocation of freed black people from Washington, D.C., to Liberia, the American colony in Africa, and to Haiti. This plan remained unrealized, but fundamentally stemmed from the widespread belief among American antislavery proponents, including Lincoln, that civic peace for whites required the departure of most freed Black people to distant places. Lincoln began changing his views on colonization only in late 1862, as he came to recognize the role that African Americans were playing, and would continue to play, in winning the Civil War.

In Washington, D.C., mainly over the course of more than three months in 1862 — in fact, claims continued to be paid well into 1863 — some 966 Washington enslavers filed their claims before the three-person Commission for the Emancipation of Slaves and received a huge reparations payment for the release of almost 3,100 captive Black people. The names of the enslavers who received cash payments are listed on this University of Nebraska website, in a project funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The list reveals an unexpected fact: Women played a surprisingly conspicuous role as enslavers. At the time of emancipation, about 40 percent of D.C. enslavers were white women. Urban slave-holding families often entrusted mobile “chattel property” in enslaved people to women, whereas titles to land property were patriarchally passed down to men. For example, in 1862, the fourth-largest enslaver in Washington was Ann Bisco, a 63-year-old widow. Meanwhile, a group of nuns, the Sisters of the Visitation in Georgetown, was one of the larger beneficiaries of enslaver compensation, for the 11 people they held captive; the nuns enslaved some 120 people in total since their founding in 1800.

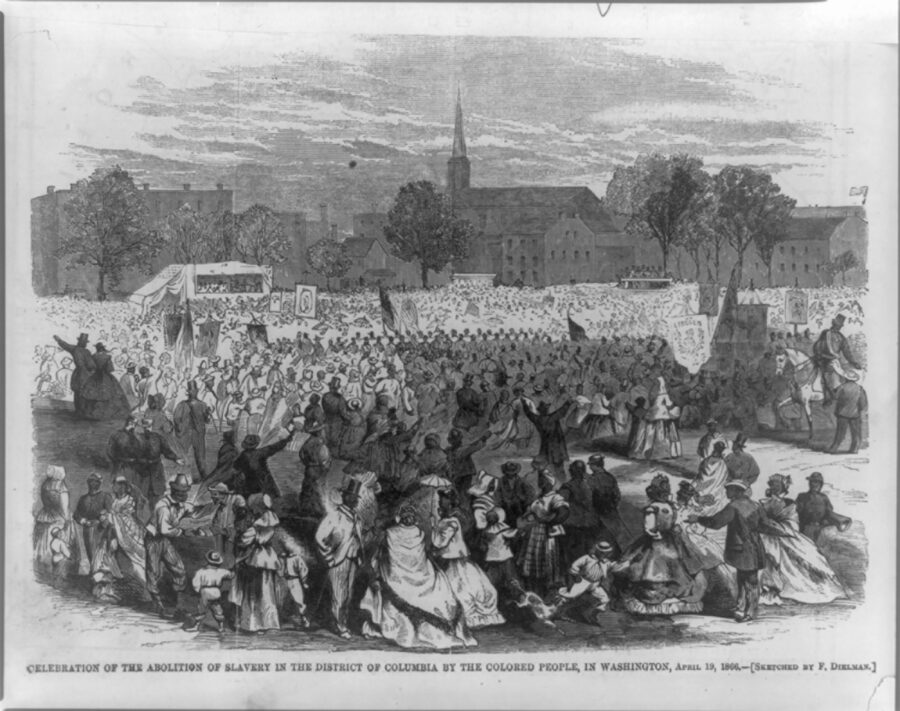

And what about the enslaved? Washington D.C.’s first Emancipation Day was certainly a day of rejoicing, yet Black people received the news reservedly, unsure of the safety of public celebration, or even of what the scope of the new freedom really entailed.

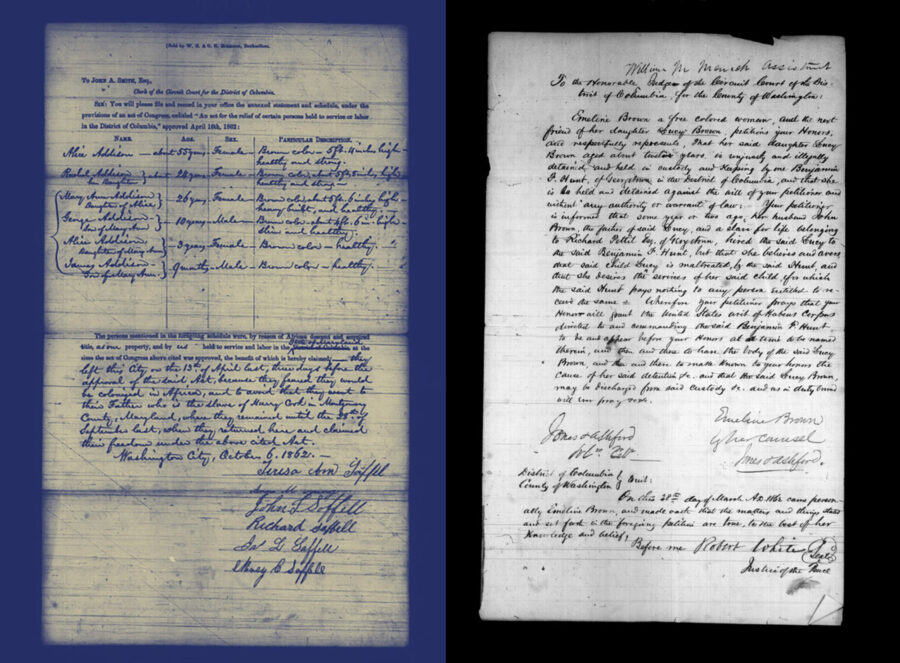

I started a participatory archiving project, open to the public, to reenvision the Compensated Emancipation records from the perspective of the enslaved, instead of the enslavers. In reviewing Washington, D.C.’s emancipation documents, it’s clear that the freedom process perpetuated the dehumanization and objectification of slavery itself. During the D.C. compensation process, modeled on the British emancipation of the 1830s, enslaved people were inventoried like property. As on the existing registers of enslaved people, enslavers listed out names, gender assignments, ages, heights, skin colors and work capacities of captive people on government forms. The U.S. government actually hired a slave dealer from Baltimore, Bernard Campbell, to certify and record the property value of each of Washington’s enslaved. Black people were categorized by skin tone, scaled according to slavery’s one-drop rule. Enslavers listed the bodily features of their captives: “slight tumor on the side,” “small feet,” “bad hands.” In order to be freed, the enslaved were priced out like pieces of human property. Enslavers concluded their inventory lists by confirming, “[my slaves are] fully worth to me the amounts [as] they are appraised.”

Not only did the freed people receive no compensation or redress, they were subjected to ongoing oppression and intimidation during the process of emancipation, and in the period after. They were forced into segregated neighborhoods, subjected to terrorization and denied legal protections offered to whites. The number of Black people in Washington, D.C., grew drastically in the years after emancipation — with more Black people per capita than any other U.S. city by 1865 — especially as Black soldiers streamed into Union’s newly established regiments of Colored Troops, and as the city became a destination for fugitive people escaping slavery in Maryland and Virginia. Black soldiers collected in Washington, D.C., and helped to win the Civil War. Meanwhile, Black fugitives from slavery in nearby states could legally be captured in the city and returned to enslavers as late as 1864.

After April 16, more than 150 D.C. enslavers still refused to let go of the enslaved people they held as captives. As of June 1862, Congress passed a Supplemental Act that allowed enslaved people to directly petition the commission for their freedom or for that of family members. Freed people sent impassioned petitions to the commissioners in hopes of rescuing their loved ones from enslavers. The majority of these petitions were granted, but around 14 percent were not. As historian Tera Hunter showed, freedom from bondage was always a struggle for Black family reunion. So, for example, John and Emeline Brown successfully petitioned in July to free their 11-year-old daughter, who was still held captive by enslaver Benjamin Hunt. Eliza Hall petitioned for the release of her brother, William Hall, from confinement by enslaver Eliza Griffith. And Basil Patterson petitioned for the freedom of his cousin, Caroline Patterson, and her 1-year-old daughter. Through petitions, people fought for the freedom of their people.

Everywhere in the Washington, D.C., records, like a pattern woven against the grain of the inventories and enslaver appraisals, is a story of Black family love. Many family groups — although torn and tangled by human trafficking — entered freedom together after April 16. Thousands of cooks, coachmen, seamstresses, carpenters and nurses crossed the threshold into freedom holding the hands of their children.

Washington’s emancipation in 1862 set the stage for the troubled general emancipation to come. Even though no cash reparations were paid to enslavers at the end of the Civil War, the idea of enslavers as the aggrieved party deserving of amends and appeasement, structured the trajectory of what would follow. This included President Andrew Johnson’s restitution of lands to enslavers in 1865, and the compromise that eventually ended Reconstruction in 1877 by giving back control over taxation, the electoral process and property ownership across the South to the old plantocracy.

When we hear the word “emancipation,” our minds go too quickly to the vision of slavery’s end. But the 1862 emancipation in Washington occurred amid the continuation of American slavery. In fact, the messiness of the Washington, D.C., emancipation — with its huge enslaver reparations, its proposed “colonization” plan for African Americans and its many examples of ongoing confinement after Freedom Day — was a portrait of the troubling character of American emancipation on a national scale. In both cases, we can point to “Emancipation Days” — but both are merely beginnings of a long, messy process that continues today.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO