The 19th Century Divorce That Seized the Nation and Sank a Presidential Candidate

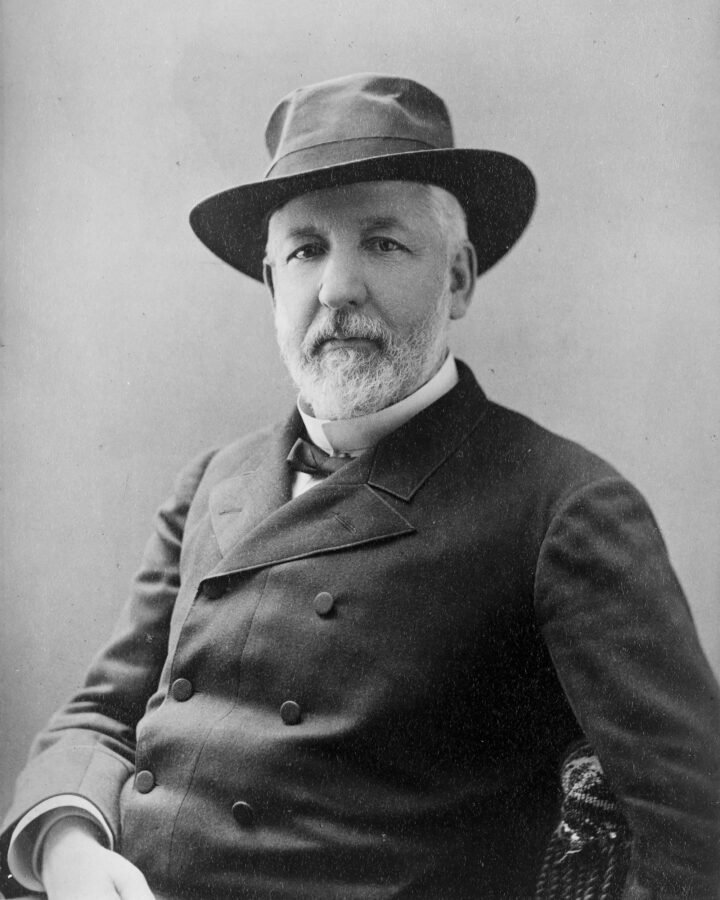

James G. Blaine, Sr. readied himself for the political battle of his already contentious career. The secretary of state would challenge Benjamin Harrison — the sitting president and a member of Blaine’s own party — for the 1892 Republican nomination. James was a seasoned campaigner and a gloves-off political brawler; he had vied for the presidency three times in the previous two decades. But he was not prepared for his true opponent that election year: an aspiring actress named Mary Nevins Blaine.

When the two had first met in 1886, Mary was not a threat to James’ political ambitions, merely a nuisance: At the age of 19, after an 18-day courtship, she had eloped with James’ 17-year-old son, Jamie, a boy he described as the “the most helpless, least responsible” of his children. The union, which both families publicly objected to at first, had been a source of much tittle-tattle as James toured the country that fall rallying support for Republican candidates. But soon, the public embraced the handsome young couple, even if James’ wife, Harriet, never had.

The impulsive marriage could, perhaps, be forgiven, but Mary’s decision to seek a divorce five years later — with a presidential election looming — could not be. That was a scandal that could torpedo a presidential campaign. James’ political brand was predicated on an unassailable private life. Faced with the scandal, he considered his options and chose silence. The family would not feed the media frenzy.

But James had underestimated Mary as a foe; the young woman knew how to use the newspapers to her advantage as well as any political pro. When he finally recognized her skills, he launched his own PR offensive in response. Their front-page fight reveals a lesson that is even more pertinent in the social media era than it was at the time: Once a story has been aired publicly, there is no way to know who will seize control of it. And the winner is often the one you least expect.

Divorce was the one of the central culture wars of the United States at the turn of the 20th century. Efforts to limit legal access allied the country’s clergy, large swaths of its political and judicial classes and many of its social leaders. For them, at this moment of rapid social and economic change, the stakes of the divorce debate were no less than the future of the American family, the very building block of the country itself. On the other side of this battle were those who did not want a fight. They wanted nothing more than release from their marriages.

A divorce was all Mary wanted, but she could not end her marriage quietly in a country of disparate divorce laws and an adversarial system that required one spouse be found guilty of a breach of the marriage contract for the other to be freed. Her divorce would be a front-page saga — some of those stories quoting Mary herself — that tarred both the Blaine and Nevins families, and it would unfold in the unexpected epicenter of the country’s divorce crisis: Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

In 1891, South Dakota had some of the laxest divorce laws in the country, and Sioux Falls had the nicest hotel for hundreds of miles. And so that spring, Mary made the four-day journey from New York City for a divorce that law and society would deny her at home. She would become known as one of the first of the “divorce colony,” a coterie of unhappy wives — for it was the women among the divorce seekers who caused the most consternation — whose personal decisions to leave their husbands forced the issue into the national conversation.

Mary lived in Sioux Falls with her three-year-old son for almost a year — the state law’s required 90 days to gain residency and then the months it took her case to make its way through the courts. Throughout that time, the intimate details of life in the Blaine family played out in the newspapers. In court filings, Mary accused Jamie of abandonment and neglect, but the headlines painted a portrait of a wayward boy spoiled by his family and forgiven for every blunder.

Jamie had been widely known as the black sheep of the Blaine family since he had been kicked out of at least three preparatory schools for, the newspapers gleefully reported, drunkenness, petty theft and dalliances with the chorus girls. At 23, his continued bad behavior ensured the Jamie was not welcome in good D.C. society, but his father still seemed determined to ignore his son’s drinking, flirting, fist fights, inability to hold a job and crippling debt.

James had begun to gear up for a fight, sending a private investigator to pry into Mary’s life. When Mary appeared in a South Dakota courtroom in February 1892, some 250 people turned out to watch what was sure to be fiery divorce proceedings — but the Blaines did not appear in court. The family acquiesced to the divorce in hopes of forestalling further gossip.

The approach did not work. When the judge awarded Mary her divorce decree, custody of her son and alimony, he also delivered a stunning rebuke not just of Jamie — “reprehensible,” with a “hardness of heart” and “reprobacy of mind” — but of the entire Blaine family for its role in climbing divorce rate. From the bench, in front of eager reporters, the judge declared, “the cause of the estrangement and separation, so far as the court is able to judge from the testimony, was the unfriendliness on the part of the family of the defendant.”

James G. Blaine Sr. was a master orator. On the stump, he commanded attention like a leading man standing in the spotlight. But before he was a politician with a national platform and the ability to draw thousands to a rally, James had been a journalist, and he still often turned to the pen to make his case. In his Senate days, James had pioneered the art of the Sunday night news release. Knowing from personal experience the difficulty of filling the Monday morning edition after a quiet weekend, James picked that moment to send statements or share his correspondence with friendly papers sure to print them as news. In this way, his voice reached not thousands but millions. Over the years, he used this platform to inform the public about his travel plans, his health and his candidacy for high office.

In the days after Mary received her decree, James sat down again to write. James had stayed mum while his family’s private matters played out in the papers, but silence had not proven to be a winning strategy for the man known for his conversational excesses. The statement of the court made clear to him that he had underestimated Mary and the effectiveness of her story. And so, on Sunday, February 28, 1892, James released “a personal statement” to the press. The next morning, it filled two full columns on the front pages of the country’s newspapers.

The Blaine family had been maligned in a South Dakota court, but James would appeal the ruling to the court of public opinion. With the love letters that Mary wrote to his son in the early days of their courtship as evidence, James penned an indictment of the young woman — and any woman who would avail herself of the courts to find freedom from her husband.

James’ youngest son’s behavior — enough to “turn the feelings of every moral man in the country,” Mary’s lawyer had warned — had given Democrats ample ammunition against candidate Blaine, and now James sought to change the narrative.

James claimed Mary had tricked his son into marriage: “It was thus that a boy of seventeen years and ten months, in some respects inexperienced even for his age, was tempted from his school books and led to the altar by a woman of full twenty-one years” — Mary was only 19 on her wedding day — “with entire secrecy contrived by herself and with all the instrumentalities of her device complete and exact.” And he wrote that “disaster is the only legitimate conclusion” of such a union. As for Jamie, James shrugged: “When his youth, his uncompleted education, his separation from the influences of home, the exchange of a life full of hopes and anticipations for premature cares and uncongenial companionship, are considered, I hold him more sinned against than sinning.”

James likely expected that to be the last word on the divorce that plagued his family name and his political ambitions, but two days later, Mary released her own carefully crafted open letter. “I acknowledge your well-rendered, richly deserved fame as a diplomat, and appreciate fully the weight which your utterances possess — as fully as do I appreciate my own weakness and my total inability to cope with you in a personal encounter but I shall expect from you that considerate and honorable treatment which I am sure your keen sense of equity and fairness will dictate,” Mary wrote. “The powerful man of a great nation will surely accord to a weak and defenseless woman her full meed of justice.” She issued an ultimatum: “Have the kindness to publish in connection with your statement the full text of the letters you have quoted from. Do not, like a shrewd and unprincipled person, select only such pages as may be needed to make your case,” she wrote. She gave him 10 days before she promised to publish Jamie’s letters to her in full.

It was a risky game of brinkmanship with the country’s top negotiator, and Mary still had a lot to lose. She had no source of income except the alimony Jamie, pleading poverty, was unlikely to pay, and any prospect of a future on the stage — or of finding a respectable new husband — hinged on rehabilitating the reputation James was further destroying. But with her legal obligations to the Blaine family dissolved, Mary was no longer powerless, and she was not a good enough actress to fully obscure that truth. “I wish it distinctly understood by you,” she wrote to James, “that I am not asking sympathy. I respectfully demand justice.”

To the disappointment of those anticipating the showdown as if it were a prizefight, Mary’s deadline passed without a word from either the Nevinses or the Blaines. The letters Mary had demanded James publish in full remained hidden, as did those she had threatened to release. They had seemingly fought to a draw. Each had inflicted serious wounds on the other’s reputation and prospects; it remained to be seen if those blows would prove fatal. It had all sent Mary to her sick bed again with nervous prostration. James was felled by the grippe and sweated through dangerously high fevers for several days.

Both had suffered self-inflicted harm too. James, friends reported, was “extremely sorry that he ever attempted to wash his family linen in public.” He had released his tirade on Mary without consulting these friends, and they believed he had made “one of the greatest mistakes of his life.” Political observers were surprised by the tactical error the consummate campaigner had committed. In his tirade against Mary, James had also attacked the country’s Catholics, a valuable voting bloc already wary of the candidate. Even those who understood James’ need to defend his family opined, “Nevertheless, it is true in such cases that ‘silence is best and noblest to the end.’”

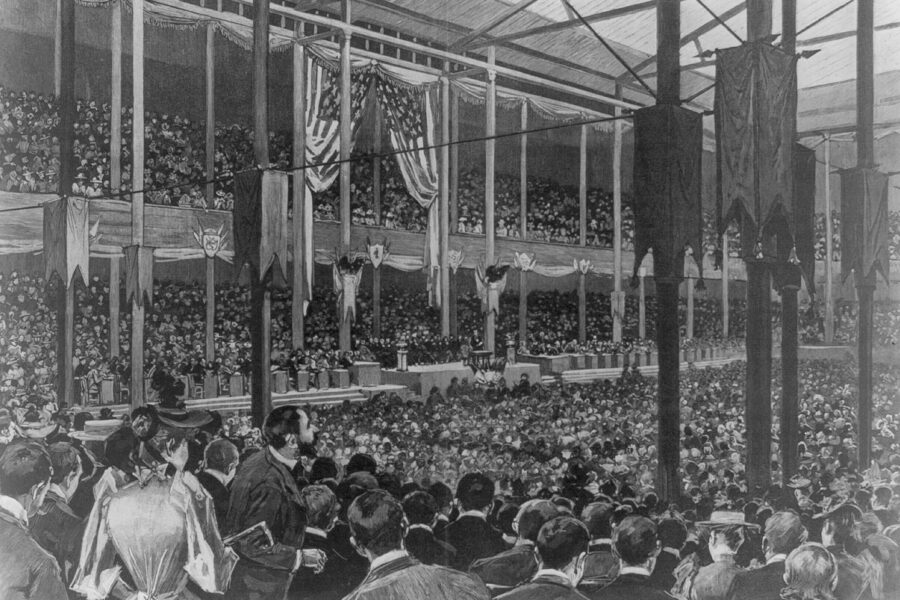

James turned his attention to Minneapolis, where the Republican Party would gather in early June to select its nominee for the 1892 presidential election. On June 4, James resigned from President Benjamin Harrison’s cabinet in preparation for his campaign. He had carefully orchestrated the convention, filling the leadership positions and the hall seats with boisterous supporters. When his name was put forward, a roar of support went up. For 60 seconds, the proceedings came to a halt as feet stomped and hats and handkerchiefs waved to the chant of “Blaine! Blaine! Blaine!” Later in the proceedings, when another supporter rose to extol James’s candidacy, the room echoed with the Blaine name for a full 30 minutes.

But the pageantry wasn’t enough. The party decisively renominated Harrison. James would not be president — and he would never escape the shadow of his son’s divorce. At the height of the convention, with thousands cheering his name, James was forced to deny a very detailed accusation about the letters Mary had sworn to publish. It was said that months of negotiations between a Nevins family representative and Secretary of War Stephen Elkins, a longtime Blaine confidant, had produced a settlement. Multiple sources insisted that $65,000 — raised by Richard C. Kerens, a Republican politician from Missouri, and five other dedicated Blaine men — had purchased the potentially damaging letters. James challenged the story.

On June 8, a Wednesday night, he released a letter addressed to the editors of the New York World: “Will you please state in your columns that it is utterly false that I, or any one for me, or in my name, ever paid or offered to pay, Mary Nevins Blaine, or any one for her, 1 cent, or any other sum for any alleged letters she holds.”

The truth of the situation never came out, but that mattered little to the public. In the campaign between the divorcee and the diplomat, Mary was declared the winner.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO