The Clintons’ MasterClass On Vanity

“My fellow Americans, today you sent a message to the whole world,” Hillary Clinton declares. “Our values endure, our democracy stands strong, and our motto remains ‘e pluribus unum’ — out of many, one. We will not be defined only by our differences, we will not be an us-versus-them country. The American Dream is big enough for everyone.”

It was the victory speech that she never got to give on election night in 2016. Instead of delivering it to screaming supporters, Clinton read it to a room of masked-up camera operators and producers, all working for the online education company MasterClass (who politely clapped at its conclusion), backed by a heavy-handed piano track. Reports on how MasterClass compensates its teachers suggest Clinton was paid at least six figures up front, plus a revenue cut for her full course, which the company released in December of 2021.

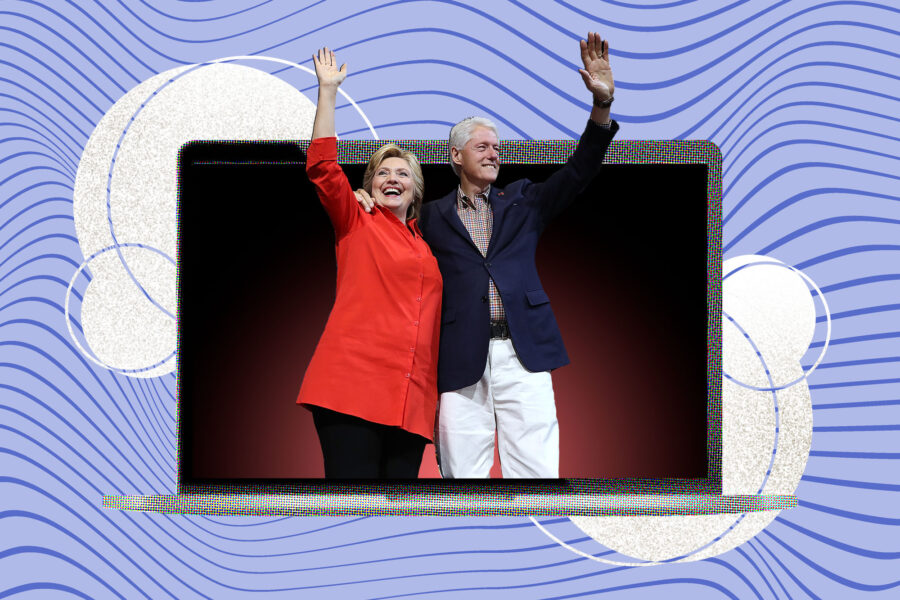

It’s pretty clear why MasterClass, a web-based platform that produces video tutorials helmed by experts in their respective fields, wanted Clinton as an instructor: The publicity from her reading her speech drew more eyes to the platform, which was valued at $2.75 billion in the spring of 2021 according to CNBC. But students may wonder just what kind of wisdom Clinton — and fellow political leaders like her husband, Bill, or George and Laura Bush, who have their own course on leadership coming — are prepared to impart. War stories have always been an academic staple, but MasterClass promises specific knowledge and expertise, such as design tips from Marc Jacobs or a primer on astrophysics from Neil deGrasse Tyson.

The question is relevant because these times, more than any other in memory, have raised questions about whether political leadership is a skill that can be learned or a gift to be used or abused. MasterClass certainly is in the learning camp, suggesting students can pick up professional tips from political leaders just like from designers or writers or sports stars.

But rather than reveal the secrets of success in politics it buries them under a load of platitudes. MasterClass skips over the whole question of how and why political leaders emerge to talk instead about more amorphous concepts like leadership and resilience. This leaves viewers with courses that are dressed up but empty. Without many concrete lessons to teach, save some bits on public speaking (there’s some bitter irony there too, as Hillary tells viewers to practice speaking in front of a mirror, and then lessons later says that she has never read her victory speech out loud), the Clintons resort to messages we’ve mostly heard before, maybe at a mid-budget hotel conference complete with a cold breakfast buffet. Make your bed in the morning. Stay organized. Define your own values. Find your own leadership style. Know your audience. Look for win-wins when negotiating.

As if to convince themselves, the Clintons are constantly justifying their presence on MasterClass with high-flying anecdotes — at one point, Hillary talks about why you should work hard, but not too hard, and uses the time she fainted into a car during the 2016 presidential campaign while she had pneumonia as an example of pushing it too far. At another, Bill uses the example of sending troops into harm’s way to explain how, while some decisions are necessarily lonely, you shouldn’t make loneliness a virtue.

The ambivalence at the heart of MasterClass’ political tutorials — with political leaders talking about everything but politics, which itself might not even be teachable — mirrors a broader ambivalence about the role of America’s politicians in its cultural life. Faith in our institutions has declined while politicians themselves have achieved greater celebrity status. If the Clintons are reaching more people via MasterClass than your average motivational speaker, it’s because they are celebrities, not politicians. At a moment when Americans are hankering for “political outsiders” and candidates sell themselves as “disruptors” in Washington, MasterClass’ pivot to politics raises far more questions than it answers: Who do we expect our politicians to be? Experts or celebrities? Technocrats or ideologues? Interested in protecting conventions or winning elections? Mouthpieces of the collective will, or talking heads with the latest talking points?

MasterClass hasn’t made up its mind.

We haven’t, either.

Launched in 2015, MasterClass is a fast-growing and ambitious company founded by David Rogier while he was a student at Stanford and developed with Aaron Rasmussen. Its sales skyrocketed during the pandemic, and financial analysts reading the tea leaves believe the company could go public this year. Today, for the price of $180 per year, viewers can learn to write verses with Grammy Award-winning rapper Nas, practice their shooting stroke with NBA star Steph Curry, build television characters with “Insecure” creator Issa Rae or make a galette with James Beard Award-winner Alice Waters.

Rogier has lofty aspirations for MasterClass. In a wide-ranging profile of the company in The New Yorker last fall, he indicated that he wants to build a new Library of Alexandria through MasterClass. He believes in the promise of its name — that taking courses from the service can start users on a path toward mastery of the subjects on offer.

“We want to have MasterClass in every household,” Rogier tells POLITICO. “[We want to make] it possible for everyone to learn from the world’s best across a variety of subjects.”

Any comprehensive digital library like MasterClass would be well served to include material on political life. Still, offering courses from politicians is not just about diversifying content for Rogier — he believes they do have something to teach us.

“[Politicians] have a huge impact on our lives,” he says. “They change the course of world events, make tough calls, help millions and manage through crises and conflicts none of us could even imagine. How do they make these decisions? What have they learned from them? How can we learn from them to be better leaders in our own lives?”

Nonetheless, politicians on MasterClass teach courses that are substantively different from much of the other content on offer. Navigate to the “food” section of the platform, for example, and you’ll find many celebrity chefs taking you step by step through how to shop and how to prepare some of their most famous dishes. These courses can serve, essentially, as instruction manuals.

Then, there are classes that combine direct instruction with some broader life lessons. If you’ve never picked up a tennis racket, watching Serena Williams talk about hitting punishing forehands isn’t going to make you a Grand Slam champion. You might gain something, though, from her approach to mental toughness, and you might remember her groundstroke lessons should you pick up a racket. Or, her MasterClass might encourage you to start playing tennis in the first place.

The politicians on MasterClass situate themselves even further into the purely theoretical. Dominique Ansel will simply teach you how to make pastries, while Simone Biles has lessons both on how to master the uneven bars and to overcome fear. But the Clintons mostly forgo political analysis, instead centering their lessons almost entirely around concepts like organization and resilience.

For students, the attraction to politicians on MasterClass, then, is not to figure out how to win an election, but to get a peek behind the curtain into their lives. This is what Rogier is offering in his political classes. Not the chance to write like Aaron Sorkin or play cello like Yo-Yo Ma, but the chance to be inspired by, and connect to, celebrity.

MasterClass believes that Bill Clinton can teach leadership and Hillary Clinton can teach resilience because of the demands placed on them while in the public eye. According to Rogier, “we’re able to put our members in the Oval Office so that they can see how these leaders act and also decide how they themselves want to shape their own leadership style.”

Unfortunately, rather than really explore the contours of their decision-making, the Clintons — who seem to not realize or not care that they’re in the stage of life when they can offer hard, revealing truths — are more concerned with molding their images. Part of Bill Clinton’s course makes it clear exactly how far into the Oval Office viewers really get.

With his distinctive Arkansas twang, the former president offers his students a personal story from after he left office.

Popular in Haiti for helping to return democratically elected Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power while he was president, Clinton stayed involved in the country after leaving the White House. So, about 10 days after the 2010 earthquake that devastated Haiti, Clinton returned to the island nation.

On one side of a major thoroughfare, according to Clinton, artists set up shops to sell their wares to tourists. Clinton was surprised to see, so quickly after the earthquake, that some of the artists had returned. He decided to show his support by buying some art. As Clinton walked back to his car, he heard a voice from the back of the crowd.

“President Clinton, don’t go. You came here in 2003 and bought something from me, you have to do it again,” the man said, according to Clinton. The artist had a picture of the two of them together from that previous visit.

“It’s good to see you again, I just can’t believe that you all have come back here so quickly,” Clinton replied.

“I had nothing else to do, because my wife and children were killed in the quake,” the artist told Clinton. “I’m in bad shape, but I know we are a family here, we artists. And we represent something about our country to all these people. They already all know what happened to me, and they know if I can be back here, they should be too.”

Clinton concludes in his course, “I have to do my own version of hanging up the paintings. We all do.”

It’s a good anecdote about leadership in the face of tragedy. Clinton tells it well. It’s the sort of story MasterClass was surely looking for when they agreed to a deal with the former president.

The problem is, the story doesn’t end there. The recovery, which the Clintons helped to lead, was in many respects a failure. And while the Clintons’ political opponents have generally overstated their personal role in Haiti’s continued struggles, Kim Ives, the editor of the largest Haitian weekly newspaper, Haïti Liberté, admitted in 2016 to the BBC that “a lot of Haitians are not big fans of the Clintons.”

What accounts for those failures — and what might they say about politics as the art of the possible? Clinton isn’t saying.

The elephant in the MasterClass room, as in much of politics today, is the result of the 2016 presidential election. Donald Trump’s victory — following that of Barack Obama, notably another candidate who built a fervent fanbase based in part on identity and ensuing celebrity — changed the image of American political leadership.

The appearance of politicians on MasterClass coincides with that ultra-celebritification of politics. Nowadays, fandom is more likely to draw students to the Clintons, George and Laura Bush, and even fellow MasterClass instructors Madeleine Albright and Condoleezza Rice than any real belief these politicians can teach a mastery of politics or policy.

“Fundamentally, this election challenged us to decide what it means to be an American in the 21st century,” Hillary Clinton said in her victory speech. “And by reaching for unity, decency, and what President Lincoln called the better angels of our nature, we met that challenge.”

This is, of course, an alternate history. She lost to a game show host. Today, Mehmet Oz is running for Senate. So is J.D. Vance. Serious liberals have suggested half-seriously that the Democrats should run Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson in 2024 or 2028. In April of 2021, he was polling at 46 percent. In addition to celebrities running for office in larger numbers than ever before, the incentive structure in politics has changed. Democratic primary hopefuls in 2020 spent the campaign desperately trolling for a viral moment. Electoral success requires an easily definable brand.

Hillary Clinton is part of a dying class of American politicians — one more comfortable talking policy than showing personality. She and Bill have also been celebrities for a long time. Whether they mean to or not, in their MasterClasses they are wrestling with those connected and contradictory phenomena. They are politicians interested in explaining politics, and also celebrities tasked with teaching other people how to be more like them.

But the sort of brand-building that led to the rise of Trump and still dominates this political era is beyond the remit of the politics courses on MasterClass. Instead, the Clintons unintentionally teach other lessons. Set your own agenda. Insist on soft lighting. Mete out vulnerability in small doses. Never turn down a big check. Keep your thoughts on your public embarrassments private. Above all, protect your image.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO