Why We Can’t Turn the Corner on Covid

The summer of 2021 began with such promise. On Memorial Day, the traditional start of summer, many Americans thought that the worst of Covid might be over, that masks were out and hugs (or more) might be in. But that optimism has yielded to a more somber and uncertain Labor Day as hot vax summer turned into hot spot autumn.

In the three months in between, the vaccination drive hit a wall of resistance, and the more infectious Delta variant arrived. All that talk about “emerging” from the pandemic morphed into nervous questions: When will we reach a turning point in combating Covid 19? When and how will we finally get back to something close to “normal” for more than a season?

Unfortunately, public health officials say that’s the wrong question. There will be no quick and clear turning point ahead in the Covid-19 pandemic, no “X” to mark on the calendar indicating that the worst is past and we can be confident that going forward there will be fewer cases, fewer deaths, fewer hospitals stuffed to their dangerous limits.

The deadly surge currently raging in the Southern states may level off, but as the virus recedes in one part of the country, it may explode in another. Public health officials are already warily watching an uptick in the Dakotas, possibly linked to last month’s Sturgis Motorcycle Rally. The governor of Idaho is summoning the National Guard to assist in rapidly filling hospitals.

It seems the narrow window to wipe the coronavirus completely off the face of the globe has slipped through our unvaccinated fingers.

But just because we aren’t looking at the best-case scenario, doesn’t mean that we’re now in a worst-case scenario. Instead, according to U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, we’re looking at something in the manageable middle.

“It is really important that we convey that success does not equal no cases,” Murthy told POLITICO in an interview. “Success looks like very few people in the hospital and very few dying.”

With all the worry about Delta, he noted, the gains we’ve made are sometimes forgotten or diminished. The vaccines do work, he stressed. Breakthrough cases remain infrequent; few are life threatening.

“This is obviously a very difficult part of the pandemic,” Murthy added. Delta is a genuine danger, but vaccinated people may overestimate their peril, just as unvaccinated people may underestimate it.

“This is the dichotomy developing,” he said. “It’s almost like living in two different Americas.”

This uneven picture will pose political challenges. Joe Biden has staked much of his presidency on getting the virus under control. He’s missed a few self-imposed deadlines but his administration has gotten tens of millions of Americans vaccinated, reopened schools and presided over a recovering economy. He’s generally had a more consistent, science-based response than former President Donald Trump did — although lately he’s angered some FDA officials by getting ahead of them over decisions about booster shots.

In his July 4 celebration of Covid Independence, Biden did warn of the risks ahead, even name-checking the Delta variant. But overall, his tone was exultant.

“This year, the Fourth of July is a day of special celebration, for we are emerging from the darkness of years; a year of pandemic and isolation; a year of pain, fear and heartbreaking loss,” he said in a speech on the White House’s South Lawn.

Now, frustration with the disease’s resurgence — coming at the same time as the messy withdrawal from Afghanistan — appears to be a factor softening Biden’s previously stable approval ratings and adding to Democrats’ worries about retaining their slim majority in the House and Senate after the 2022 congressional elections.

The months ahead will undoubtedly be a mix of advances and setbacks. The political challenge for Biden and the public health system will be to communicate a sense of progress and momentum even without the benefit of a clear “turning point.”

The halcyon days of late spring and early summer weren’t a mirage. It really was better. Cases were down, deaths were down, hospitals were more or less back to normal. Even in communities with low vaccination rates, the virus was in retreat. As former White House coronavirus adviser Andy Slavitt put it, you could walk around anyplace in the country and just not be all that likely to encounter someone who could infect you.

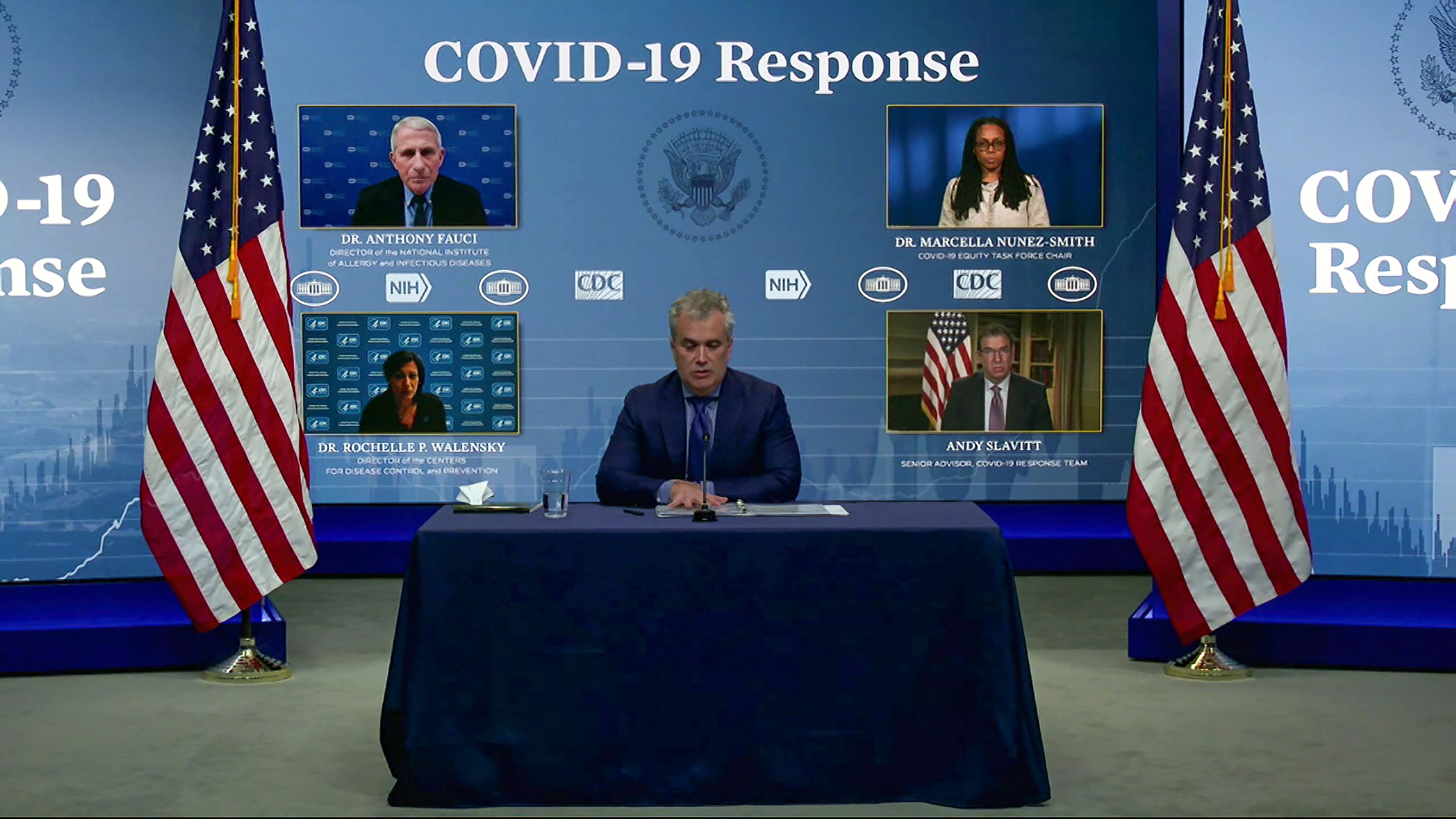

Centers for Disease Control Director Rochelle Walensky was second guessed in some quarters for going too far, too fast when she told vaccinated people in May that they didn’t have to wear masks. (Many of the unvaccinated had already scrapped them, if they had even worn them in the first place). Critics said she confused the public, and that she should have linked mask guidance more closely to local vaccination rates. But Walensky wanted to encourage vaccination — and going mask-free was seen as a lure for the hesitant.

Yet that moment in time, that glimpse of normality, was a tentative “so far, so good” truce with a mutating virus. Even as things got better in the U.S., the variant now known as Delta was tearing through India, sending thick plumes of smoke from the funeral pyres. Soon it was here, and “so far, so good” wasn’t so good anymore.

Epidemiologists now expect the coronavirus to be endemic, meaning it’s here to stay. But even if the virus persists, it doesn’t mean a perpetual pandemic. Over time, human immunity will keep growing through vaccination and natural infection; that’s already started. Scientists will develop new treatments. Eventually, Covid can become one of many diseases that circulate, that sometimes even kill, without bringing the world to a deadly standstill.

Until then, the challenge is to find out how to co-exist with it, tenuously, as safely as we can.

For the indefinite future, fighting the pandemic is more like a tug of war than an epidemiological ground war. We just have to keep tugging harder than the coronavirus does. Sometimes we’ll tug our way into periods of relative normalcy, like last June and July. Sometimes it will tug us back into moments like right now — not hunkered down the way we were before vaccines but still making a constant, exhausting chain of risk assessments and adjustments as we try to reclaim as much of our lives, economic and emotional, as we can.

“You make calculations in your brain all the time… We start to manage challenges,” said Slavitt. “I can see my mom, I can take this trip, I have to do X, Y and Z but I can do these things and live my life.”

Part of what we’ll need to do is assess the unevenness around us. Hotspots will come and go all across the country, and we’ll need to keep track.

“If I’m getting on a plane to Buffalo, I normally check the weather to know what to pack. But now I’m also going to check and see what the Covid situation is in Buffalo,” added Slavitt, in a phone conversation far from Buffalo. “I think the nuance is — things will be different in each location. And it could change. It could change within a matter of weeks.”

Getting to some kind of equilibrium with the virus will require vigilance. For individuals, that means vaccines, and, at some times and places, masks and social distancing. Not all day every day, but when appropriate, when the virus rears its head. Vaccine rates are inching up again as mandates expand and recognition of Delta’s danger grows with the death toll — but it’s not yet enough.

“People are still in denial,” said Celine Gounder, an infectious disease specialist and epidemiologist at NYU and Bellevue Hospital, who advised the Biden transition team. “The sooner people accept the changes in the way we live… the sooner we can get to the new normal.”

For public health, maintaining that equilibrium means maintaining testing capacity, data collection, contact tracing and genomic surveillance. Generally, those tools, though still imperfect, are far stronger now than they were in the early months of the pandemic under the Trump administration. The Centers for Disease Control won plaudits recently for kicking it all up a level by creating the Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics, staffed by some of the nation’s top experts. “It’s the A team — it has the potential for changing the CDC’s approach,” said Mark McClellan, a former FDA Commissioner who now leads the Duke-Margolis health policy center.

Keeping the virus at bay will also require focusing a lot more attention on improving and expanding access to treatments, particularly medications that can be taken orally outside a hospital or infusion center, McClellan and other experts say. In one bright spot, the monoclonal antibodies that are currently available, which do have to be injected or infused, are coming into broader use and saving lives. White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator Jeff Zients announced this week that 670,000 courses of monoclonal antibodies were shipped in August, “six times as many as we shipped in July.”

“I’m a big fan of the monoclonal antibodies,” said West Virginia Health Commissioner Ayne Amjad. These treatments are lab-produced versions of human antibodies that target the coronavirus, often preventing infected people from becoming seriously ill. Trump was treated with monoclonal antibodies when he got Covid last fall.

Amjad is trying to make the injectable version much more accessible in her state, including through home health agencies and mobile vans that are doing coronavirus testing and vaccination — theoretically, a mobile van could test you for Covid and if the test is positive, immediately give you a shot of antibodies. In the meantime, she’s also trying to raise public awareness so at-risk people know to ask health providers for it; the treatment works best if administered in the first few days after exposure.

Delta is more dangerous to kids than prior versions of the coronavirus, and kids who aren’t old enough to be vaccinated may also spread it. So schools are going to be a flashpoint. In fact, schools already are a flashpoint, as shown by the legal and political wars over mask mandates, in some cases driven by Republican governors like Florida’s Ron DeSantis with presidential aspirations. More battles are likely as school systems try to enforce — or forego — quarantines when cases are detected.

Navigating the new school year — which overlaps with many office reopenings — will require a lot of nuanced public health communication — and nuance is not the strong point of the American public. In a politically riven country, where even those who accept and recognize the Delta threat crave certitude, parsed statements from public health officials like “up to a point,” “the science is evolving” or “we’ll have to wait and see” — are not the medical comfort food people seek, particularly where their kids are concerned.

That makes messaging hard, especially when some Americans see changes in public health communication as lying or betrayal, not the natural outcome of learning more about a hitherto unknown disease. The changing guidance around masks is part of why a segment of the public turned on Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease doctor and a key Biden adviser.

“We are continuing to learn about the virus and vaccination and our guidance and recommendations have to change and keep up,” Murthy, the surgeon general, said. “What we have to do is make sure we’re communicating clearly and transparently about what’s changing and why it’s changing. It’s easy to say, harder to do.” It requires making the public understand both the ongoing risks, as well as the steps they can now take “to see family, to see friends, much more safely.”

As grim as Delta is, there has been progress, above and beyond vaccination. Many policy levers have already been pulled, although they can still be fine-tuned and expanded.

That new CDC analytics center should be able to track new variants, making it less likely that an Epsilon or Zeta will clobber us as hard as Delta has.

The monoclonal antibodies, combined with steroids and other medications used in hospitals, are saving lives, even though more treatments are needed, here and abroad.

Testing labs are for the most part keeping up with demand amid the surge, and the government just invested $200 million to boost supplies of rapid tests people can take at home (or work). But to be a game changer, the price has to come way, way down, said Gounder. “Nobody wants to spend $25 per person per day. If we could get them down to a dollar apiece” people could test before a dinner party, before a play date, before a visit to Granny and Grandpa.

There’s a better understanding of how to manage even big events, with vaccination, testing and masking requirements. There was a lot of trepidation about Lollapalooza in Chicago earlier this summer, but according to city health officials, there were about 200 cases among the 385,000 attendees. Half were breakthroughs; the unvaccinated (who had to present a negative test taken within 72 hours of attending) were at higher risk of getting sick. Masking, which was not required throughout the festival, might have added another layer of defense.

Some countries have done things like distribute free or cheap masks but, as Gounder noted, if the U.S. did that, “I could see in this country people have bonfire of government-donated masks. That wouldn’t be good either!”

More and more businesses are requiring mandates of one kind or another — vaccination, testing, masks or some combination — but some business owners might shun them, fearing it would anger or alienate customers in communities where Covid is still seen as a hoax, or where mandates are seen as infringements of liberty.

There are government funds for ventilation and air filtration that communities haven’t yet tapped, partly because it’s complicated and requires significant expertise, said Gounder.

But policy can only get so far. Much of the tug of war will go on in people’s hearts and minds.

“I don’t think it’s going anywhere,” West Virginia’s Ahmed said of the virus. “We’re going to have to learn to live with it and find ways to deal with it. And not make it so politicized, dramatized and make people so upset.”

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO