Opinion | ‘Anyone Got Any Helos Sitting Around?’: How a Private Network Is Using a Messaging App to Rescue Afghans

The Signal channel begins to heat up late at night.

In the hours before dawn in Kabul, before the daily crush and chaos resumes at the airport where tens of thousands of desperate Afghans and American citizens vie to reach transport planes on the other side of armed gates, the members of the #AfghanEvac group share information they hope will enable friends and former colleagues to escape the reach of Taliban revenge.

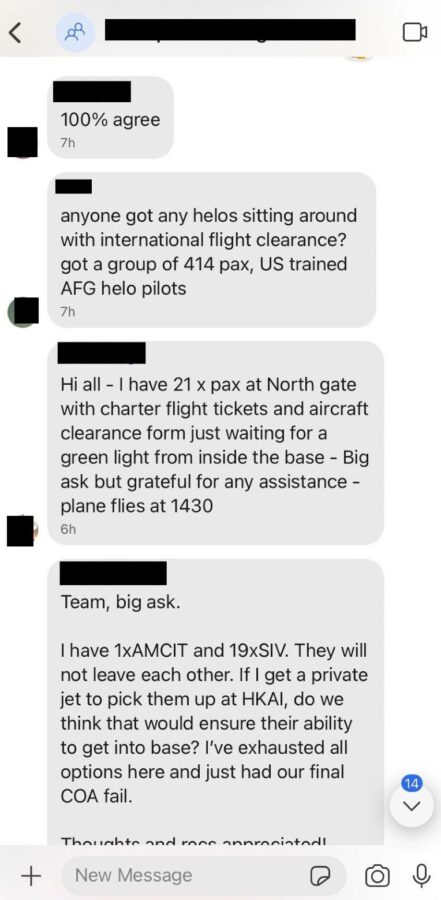

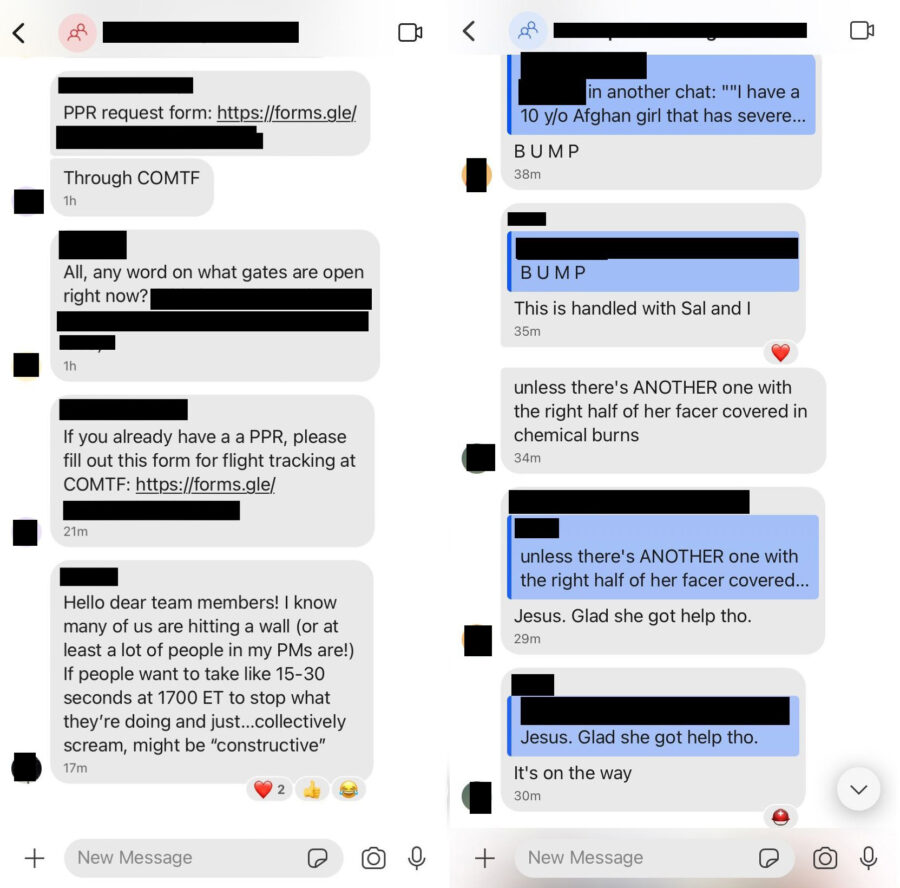

The chat is frantic, a hypnotizing, disorienting kaleidoscope of spy-thriller drama (“anyone got any helos sitting around?” “I have one American citizen who won’t abandon his family of 15. If I secure a private jet, can we get them into the base?”); grinding logistical minutiae (“Can anyone remind me where the petrol station is near Abbey Gate?”); jerry-rigged efforts to paper over failures of traditional leadership (“I’ve been pushing DC admin for solutions…here is a draft of a giant poster we could make to show who is being let in where”, “Use visual markers so people can be picked out of the crowd. Balloons have been working well — kids carry them to the gate and then parents can lift them up for visibility”); and gut-wrenching personal details (“Please delete any tweets with my handle. I am getting death threats and need to have my phone free,” “lone female with no food or water for 48 hours, multiple fainting spells over last 24 hours,” “I have my entire family trying to get in! What do I do? There are 3 babies!!!”)

On balance the desperate appeals far outnumber the responses that proffer actual help. Even former chiefs of staff to Cabinet secretaries find themselves begging for basic info: “any word on what gates are open right now?” Nevertheless, the diverse group of volunteers — veterans, Hill staffers, private sector employees, members of the intelligence community and human rights advocates — persists through disappointment, frustration, and panic. Driven by anger at their own government’s failures and haunted by personal experience in the decades-long conflict, participating in the #AfghanEvac group is a chance at redemption, to wrench something meaningful from the wreckage of “nation-building.” One member describes it as “the finest organization I have been a part of.”

I joined the group on August 20, for much the same reason as the rest of the roughly 100 members of the group: The man who served as my interpreter in 2009 when I led a platoon of soldiers in Kandahar Province, who risked his life for me and my men, is in mortal danger.

I have been in touch with “Rock” (for his safety, I cannot reveal his real name) for years, but the pace of our communication has picked up dramatically since the Taliban came back to power. The members of #AfghanEvac helped me guide Rock from the northern province of Kunduz, past Taliban checkpoints (a map has circulated on the channel that shows Taliban checkpoints around the capital, almost like Waze for refugees) to a safehouse in Kabul where he was able to renew his Afghan passport.

But he remains stuck on the wrong side of the walls at Hamid Karzai International Airport.

One active-duty service member working for #AfghanEvac describes America’s evacuation in Kabul as “a full-blown humanitarian crisis…The reason we care so much is because we have invested so much over the past 20 years. This effort is a part of our identity…It represents the love and affection that people are supposed to have for each other.”

The coordination on Signal is grueling, detailed work.

It includes everything from complex tasks such as chartering planes and advocating for landing rights in foreign countries to more focused goals such as locating a law firm willing to do pro-bono visa applications. Participants on the channel have found safehouses for evacuees; coordinated safe passage for a 7-month-old U.S. citizen to get inside the airport’s barbed wire fences and located medical care for the disabled parents of a visa-pending Afghan interpreter who collapsed from heat exhaustion. The #AfghanEvac volunteers use their network of personal and professional connections to bring issues to the proper authorities where possible, but often they are left to do it themselves.

Had the U.S. government planned for this evacuation properly, the efforts of those supporting #AfghanEvac would have been wholly unnecessary. But instead, as one volunteer describes it, while working to rescue the relatives of an Afghan-American who is currently serving in the U.S. Army, we have “Saving Private Ryan: Kabul Edition.”

In the global coverage, with its gross homogenization of “waves of refugees,” it can be easy to forget that statistics conceal unique and personal stories. (One example of the depth of our ignorance: We haven’t yet determined the number of people whom we have the responsibility to evacuate, and many (most?) remain scattered throughout Afghanistan.) Imagine that you are an Afghan interpreter, like my former colleague “Rock,” with a pending special immigrant visa (SIV). Based on the photos, videos, texts and voice memos from his journey to Kabul, I have a vivid and harrowing picture of what people like him are going through.

To get to the airport, you must first face a brutal, almost entirely unsupported, gauntlet. Your risks in transit, coming from across Afghanistan, remain high and you may not have the means or even the strength to make it the last mile to the airport.

If you are fortunate enough to make it to the airport, you face disorder, fear and confusion, fueled by Taliban harassment, beatings, tear gas, shootings and stampedes. At least seven people died on Sunday during a stampede. This creates a ‘rush-for-the-lifeboats’ sense of pandemonium at entry control points. Amidst the chaos, military personnel at the gates do not apply clear and consistent entry criteria, turning away evacuees — sometimes even American citizens — with appropriate paperwork, further adding to a sense of futility and injustice. By now, you have been standing for days, weighing a mercurial security situation and conflicting rumors to choose the gate where you will wait and, nearly being smothered to death, hope that you just get lucky.

If you are one of the few with influential, dedicated friends and chance on your side, you manage to get through the gates. Inside, you are greeted by shortages of food, water and medical supplies as you wait hours to board a plane. Even in this, the best of all possible scenarios, the outlook is not certain; with significant domestic resistance to bringing Afghan citizens to the U.S., the need is great for third-party countries to take in evacuees and the rights-to-land agreements are insufficient so far.

The Biden administration has begun to trumpet the evacuation as a logistical success — 70,000 people in 10 days — but the emergency drags on and it should never have been allowed to reach this point in the first place. I have appealed to Rep. Stephen Lynch (D-Mass.) on behalf of my interpreter for years without success. I got this update from Lynch’s office earlier this week: “Administrative processing of Special Immigrant Visas will continue and applicants will continue to be notified about the status of their cases.” In other words, no progress.

The evacuation in Afghanistan did not have to be this disastrous, the Biden Administration can still take steps to save lives:

First, immediately resolve pending visa statuses and have the Secretary of Homeland Security, Alejandro Mayorkas, grant humanitarian parole to others. We must ensure that all eligible Afghans and their immediate families are evacuated, not just those who have been lucky enough finish the State Department’s administratively broken Special Immigrant Visa process.

Second, advocate with other countries for landing rights for Afghan evacuees. The challenge to find places to put evacuees is complex — different countries have different rules about the types of applicants they will take and the duration for which they are allowed to stay — but the burden ultimately rests with us. After all, the reason people who are currently being evacuated need to be evacuated is because they served U.S. interests during our failed war in their country.

The U.S. government failed its veterans by keeping them in an unwinnable, negative-sum war for 20 years; if it abandons our Afghan allies at the end, it will have failed us twice.

In my parting words to Rock, who stood outside the North Gate of Hamid Karzai International Airport until 4:30 a.m. on Monday, I tried to buoy his spirits.

“I imagine you will feel exhausted by the end, but I’ll do whatever I can to get you to the U.S.,” I texted.

“Thanks, sir,” he replied. “We’ll be here.”

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO