The Tragedy of the Cuomos

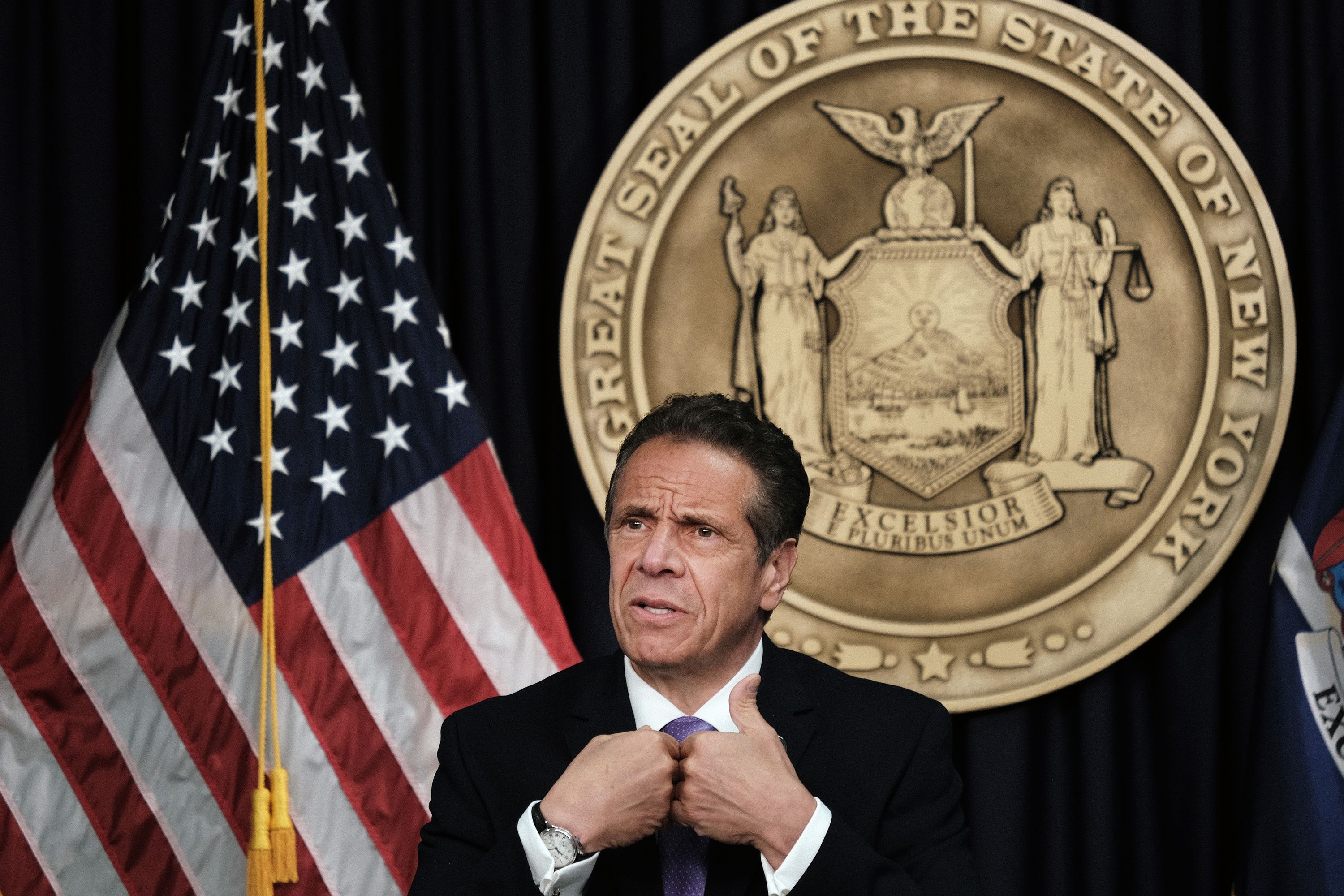

Andrew Cuomo’s abrupt announcement that he will resign as governor brings what is likely an end to New York’s latest and most enigmatic political dynasty.

Right up until the scandal hit over his alleged sexual harassment and bullying, Andrew Cuomo seemed certain to match his father’s mark of three straight terms as governor of New York, and he was a heavy favorite to win a fourth term in 2022. Yet somehow, for all their obvious political talent and moxie, for all the outright adulation they drew from Democrats and others both in and outside of the Empire State, the Cuomos never quite crested the pinnacle of American political power. No one has ever been sure why.

They had copious talent—Mario for idealistic rhetoric and management, Andrew for the raw exercise of political power. Donald Trump, who understood power, feared the latter: In the spring of 2020, he became fixated on the idea that “President Obama and his allies would soon orchestrate a coup, replacing [Joe Biden] as the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee with New York governor Andrew Cuomo,” according to Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker in their new book, I Alone Can Fix It.

“He’d be tough. So tough. I’d beat him, but he’d be tough,” Trump obsessed.

The Donald’s preoccupation brings to mind nothing so much as Richard Nixon’s abiding fear of the Kennedys. The Cuomos are an obvious analogy to the Kennedys, a clan that for 15 years they could count as in-laws: ethnic white Catholics breaking into the old political establishment. But the Kennedys made it to the pinnacle, in more than one way. Somehow, unlike the Kennedys, the Cuomos never did. They never quite even went for it.

Mario Cuomo, the political philosopher from Queens with the face of a medieval saint, set liberal hearts on fire after he was unexpectedly elected governor of New York in 1982, near the nadir of the Reagan era. At his best, he had an almost Lincolnesque ability to both inspire hope and also unpack the logic of any issue. I remember one columnist comparing him to Savonarola after his majestic convention speech in 1984, the winter of Democratic despair. His supporters worshipped him, his opponents feared him. A Republican Wall Street executive I knew at the time opined that a Cuomo-vs.-George H.W. Bush race in 1988 would be “like a Great Dane pissing on a poodle.”

Yet Mario never declared for that race, even though the Democrats had no alternative more charismatic than Michael Dukakis. He never entered the 1992 race, either, though there was legendarily an airplane fueled and idling on the tarmac in Albany, waiting to whisk him away to register for the New Hampshire primary. There was always some excuse, always some last-minute budget deal that had to be worked out in Albany, the New York State capitol, where everything is always done at the last minute, and the last minute always lasts forever.

Andrew Cuomo, despite his own high ratings as governor and numerous Democrats nationwide wanting him to run in 2016 or 2020, never even took things that far. Never, really, even sent up the proverbial trial balloons about making a run for president.

Mario’s seemingly inexplicable reluctance to run gave rise to all sorts of scurrilous, bigoted rumors that he had personal or family ties to the mob. Not a scintilla of evidence has ever emerged to that effect, then or since.

Could it have been some greater reluctance holding the Cuomos back? Could it be that, for all that they have celebrated their heritage—Mario’s story of his immigrant father saving a huge blue spruce tree on their property was a staple of his speeches—there was some residual ethnic reluctance there, a feeling that these first- and second-generation Italian-Americans still didn’t really, fully belong?

Or could it be that the Cuomos are the first New York provincials?

For the leaders of what has always been one of our most sophisticated, cosmopolitan states, the Cuomos always seemed a little ill-at-ease outside of their Albany comfort zones. It was no coincidence that Mario Cuomo was a friend and huge fan of William Kennedy, Albany’s brilliant chronicler in fiction and history. Politically, the old Albany of “three men in a room”—a remarkably retro place where for decades most of the state government was window dressing, the final decisions made exclusively by the governor with the leaders of the state assembly and senate—was always the Albany that both Cuomos, father and son, seemed most comfortable with.

Usually, that meant a tidy, centrist—some would say, corrupt—consensus worked out between both parties. It also meant a redoubt for the Cuomos where they could bully, harangue and harass their subordinates in so many ways. When liberal Democrats, outraged by the election of Donald Trump, stormed the state legislature from the left at the polls, Andrew Cuomo’s grip on power inexorably began to slip.

New York has had plenty of political dynasties in the past, going all the way back to the start of the Republic, and even before. The Livingstons, the o.g. Clintons (George and De Witt), the Hamiltons, Van Burens, Wagners, Roosevelts—and yes, even the Kennedys, through the transplanted Bobby. Yet almost always, these families were intent on grabbing for the big prize, down in Washington, and as often as not, they did just that.

Not so much the Cuomos, late of Hollis, Queens, who found their blue heaven not on the Potomac but the Hudson, in a sagging old river town. When the modern world broke in on that sanctuary—when the toxic privileges of ensconced power could be exposed to real public scrutiny—the family was done.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO