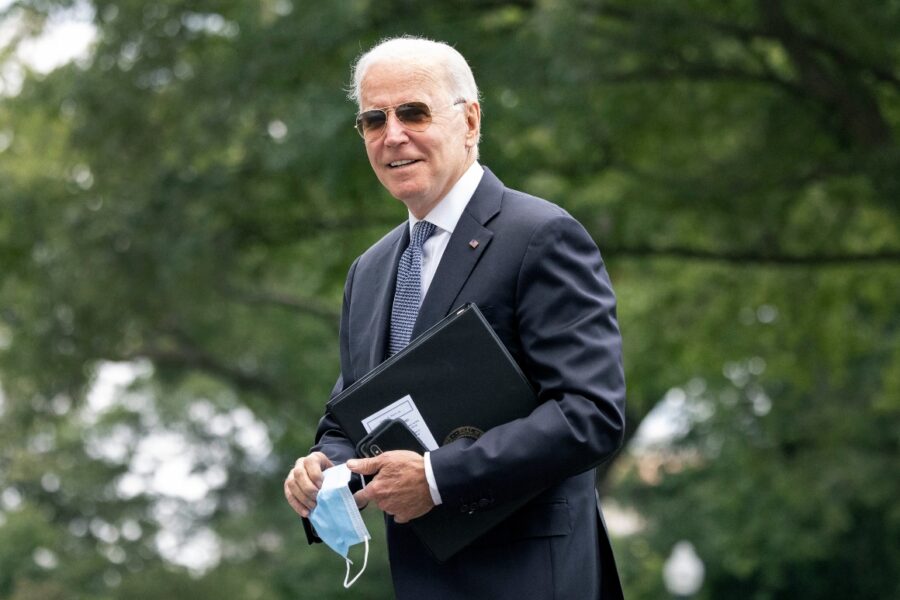

Biden’s bipartisan win leaves progressives thirsting for more

The Senate’s $550 billion infrastructure deal offers historic amounts of cash for a host of causes that progressive Democrats hold dear — from boosting mass transit and high-speed rail to addressing the impacts of climate change to closing socioeconomic divides in clean water and broadband internet service.

Yet many liberal activists found themselves caught between deflated and enraged.

No groups may feel more jilted than transit advocates, who argue that Senate Democrats and President Joe Biden are passing up a rare opportunity to wean the U.S. from its century-old addiction to road-building. Instead, the bipartisan deal (H.R. 3684 (117)) offers $39 billion in new money for transit — a sum large enough to pay for tangible improvements in the nation’s chronically underfunded transit agencies, but one that’s dwarfed by the bill’s $110 billion for roads.

“From what I can tell, this is a largely status quo and highway-centric bill,” House Transportation Chair Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.), one of Congress’ top proponents of more money for transit, said Monday in an email to POLITICO. He added: “Ultimately, we need a bill that goes bigger, bolder, and takes advantage of this once-in-a-generation opportunity to catapult our infrastructure into the modern era and beyond.”

The bill separately offers $101 billion for high-speed rail and Biden’s beloved Amtrak — a huge amount of money but probably not enough to fuel the “second great rail revolution” he promised during his campaign. And the bill largely abandons the administration’s promise to undo the wrongs of past transportation projects, spending just one-fortieth as much as Biden had initially sought to tear down or redesign highways that bulldozed through communities of color and cut low-income people off from job opportunities.

The result is a paradox for Biden, who has called for historic, transformative legislation while pledging to show he can bring a polarized Washington together. In this case, he couldn’t do both.

On many issues, progressives will be looking beyond this infrastructure bill to a larger, $3.5 trillion package that Democrats could pass without any GOP support, one that could take a larger swing at causes such as climate change. But infrastructure may not make it into such a bill, leaving the Senate deal as possibly the last word.

Some lawmakers are looking on the bright side, with Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) noting that “the investment in transit is historic.”

“Would we have liked to go further for electric vehicles or responding with sustainable or renewable energy? Yes,” Durbin said on MSNBC. “But we have a 50/50 Senate. We can only take the Republicans so far and we take what we can get.”

Here is POLITICO’s roundup of what the 2,700-page legislative package would do:

Transit

The $39 billion contained in the deal could make a major difference for transit agencies, allowing them to make a dent in long-deferred maintenance backlogs. It could also pay for improvements that would enhance their appeal to existing and new riders, such as reliable schedules, real-time tracking information and buses that come every 10 minutes instead of every 20.

But highways would remain the king of the road in Congress’ transportation spending priorities. The deal also omits policy language from a House-passed bill that DeFazio championed, which would have limited the ability of state transportation departments to build new highways or widen existing ones.

His bill would have authorized more money for transit, and more of it would have been added to baseline spending, rather than making it a one-time infusion — much like the difference between getting a salary raise or a one-time bonus.

Green groups and progressives had looked to DeFazio’s bill as a definitive policy shift that would have lessened the transportation sector’s outsized contribution to U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, they — and DeFazio — were sidelined as the bipartisan talks took place among the White House and a tight circle of moderate senators.

And transit advocates are flummoxed that when the bipartisan group went dark for five weeks after initially reaching a deal in June, the new agreement they announced last week contained a $10 billion cut for transit and few other significant changes.

Beyond the money, the House bill would have also required states to reduce their transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions and improve safety for everyone — not just for people traveling in cars.

“It isn’t about the amount. It is about what you want to accomplish,” said Beth Osborne, director of the progressive group Transportation for America. “Will building a bunch more highways and expanding more while spending still a fraction on transit address climate or equity? Can you fill a hole with a teaspoon while digging with an excavator?”

Rail

The agreement includes about $101 billion for rail over the next five years, according to a POLITICO analysis, and would offer what the White House has called the “largest federal investment in passenger rail since the creation of Amtrak.” Analysts say rail service got a bigger percentage bump in funding from the Senate deal than any other mode of transportation.

Of that sum, $66 billion is standalone, guaranteed funding — a sum that dwarfs the last injection of its kind, $9.3 billion provided in former President Barack Obama’s stimulus.

But the bill still leaves gaps that will make it difficult to force improvements in the United States’ subpar rail service, transportation experts say.

For one thing, a third of the rail money is not guaranteed — it’s subject to Congress’ annual appropriations whims, and therefore could fail to arrive if Republicans take one or both chambers of Congress. The bill also doesn’t include some deeper policy changes that Amtrak had endorsed, such as one that would have given passenger rail services more leverage over freight railroads for access to tracks — a key to ensuring better on-time performance.

And overall, the bill largely focuses on repair and upgrades, not adding new service, a source of some disappointment on the Hill.

“It will enable repair, but not real rebuilding,” said Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) on Monday. “The backlog of maintenance and repair can be addressed through this infrastructure proposal, but not the massive rebuilding that’s necessary for high speed rail.”

Climate change

The bill includes some efforts to reduce the United States’ greenhouse gas pollution — but its climate provisions focus largely on helping communities withstand calamities such as worsening floods and hurricanes, rather than trying to prevent the catastrophic warming of the planet.

One major symptom: The bill’s treatment of electric cars.

eleOf the $174 billion that Biden originally proposed to help Americans shift to electric vehicles, the compromise includes just $7.5 billion for charging infrastructure. It also includes a boost to grant money for low- and no-emissions buses, although it designates a quarter of that money for buses that produce some carbon emissions — a concession to natural gas producers.

The bill would also expand funding for innovative transportation and clean energy technology research and deployment, while also spending billions on programs backed by fossil fuel interests, such as efforts to enable coal- and gas-fired power plants to capture and store their carbon emissions. And it includes $50 million to reduce truck pollution at ports, largely through electrifying port vehicles.

Water

The deal offers $15 billion for removing lead from the nation’s drinking water systems, particularly in low-income areas and communities of color that disproportionately suffer exposure to the potent neurotoxin.

But that’s a fraction of the $45 billion that the White House initially called for to accomplish its signature goal. It’s also far less than the $60 billion that the drinking water industry says would be needed to finish the task — addressing a crisis that was dramatized in recent years by the lead contamination that fouled residents’ taps in Flint, Mich.

That hasn’t stopped the White House, as recently as last week, from proclaiming that the bipartisan bill “will put plumbers and pipefitters to work replacing all of the nation’s lead water pipes so every child and every American can turn on the faucet at home or school and drink clean water.”

DeFazio has called the president’s words laughable.

“We’re seeing a lot of spin out of the White House, which is just unbelievable,” he said on a call with reporters last week, noting that $15 billion “of course would not replace all the lead pipes.”

High-speed internet

In one of the bill’s final sticking points, the bill would provide $65 billion to expand broadband service to unserved and underserved rural and urban communities, while making internet service more affordable.

That’s an unheard of amount of money for the effort to close the digital divide, and puts internet affordability concerns at the forefront in ways Washington has never done before. But one compromise needed to seal the deal is already becoming contentious.

One major dispute is the bill’s attempt to address so-called digital redlining, in which internet providers invest more money in wealthier consumers or more profitable markets while offering slower speeds and less service to low-income customers. The final language says all consumers should have access to comparable internet services, but only “insofar as technically and economically feasible.”

That gives ISPs a lot of leeway to give short shrift to poorer and minority communities, fairness advocates argue — even as they celebrate the fact that Congress is willing to admit that digital redlining exists.

“In the past, there has been resistance to even admit that this is a problem,” said Public Knowledge senior policy counsel Jenna Leventoff. “But the current text has huge loopholes.”

Still, the final text of the bill added billions more to both the broadband grant and broadband subsidy programs than originally proposed. Subsidies that Congress created to help low-income households pay for internet access during the pandemic are also now being made permanent.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture would get a $2 billion boost to expand high-speed internet across rural America. The lack of broadband access is a major hurdle not only for rural students and remote workers, but also for farmers that rely on a steady internet connection to gain access to commodity markets and use high-tech farming practices known as precision agriculture.

A new tax target: cryptocurrencies

The bill would require trading platforms for Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies to report transactions to the Internal Revenue Service, in a bid to close what officials see as a major tax revenue gap in the digital asset market. The proposal is projected to raise $28 billion to help finance infrastructure projects.

The proposal would mimic reporting rules triggered when investors sell stocks and their brokers are then required to report the information to help determine tax bills.

The provision has set off a scramble by crypto lobbyists and advocates to narrow the definition of what constitutes a “broker” in the context of digital currency. They say it’s expansive enough to capture so-called miners that operate the infrastructure underlying major cryptocurrencies.

Health care

The package would delay a Trump-era Medicare drug rebate rule for three years, a postponement that negotiators say would save roughly $49 billion.

The rule was aimed at eliminating the rebates that drugmakers pay to middlemen called pharmacy benefit managers to assure that their medicines have preferable placement on insurance plans. Those savings, which can be as much as half a drug’s sticker price, are not passed directly to consumers, though insurers argue they use savings to keep premiums low.

Democratic leaders contend the projected price of the Trump-era policy change, nearly $200 billion over a decade, and the possibility of higher monthly premiums in Medicare made it unworkable.

Democrats are eyeing fully repealing the rebate rule in their planned $3.5 trillion reconciliation package as a way to pay for the party’s health care priorities, like expanding Medicare and closing the Medicaid coverage gap.

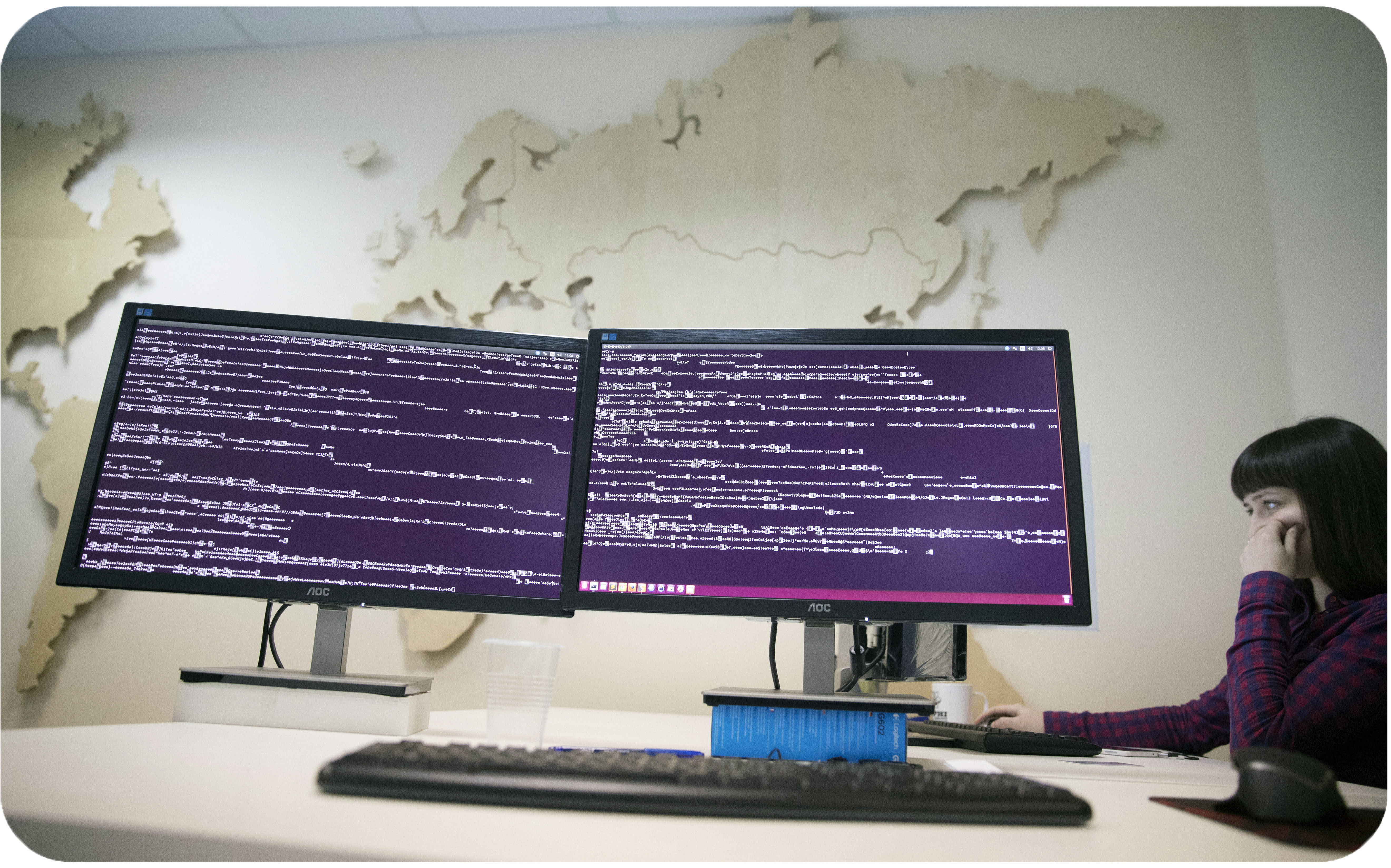

Cybersecurity

The package offers several pots of unexpected funding for strengthening government cyber defenses, most of it kept behind closed doors until Sunday night’s release of the final text. It includes $1 billion over four years for state and local upgrades, $20 million each year through September 2028 for a federal response and recovery fund and $21 million to fund the national cyber director’s office until October 2022.

The bill also requires certain operators of critical infrastructure and other grant applicants to submit cybersecurity plans when they seek federal money for upgrades of systems such as the electric grid and water treatment plants.

After Biden’s first infrastructure framework lacked any mention of security, supporters were eager to get anything into the deal. They got some momentum after a spate of high-profile attacks this year, including a ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline that prompted a five-day shutdown of much of the East Coast’s gasoline supply.

“Since even traditional ‘hard’ infrastructure now has a significant digital component, including cybersecurity provisions not only makes sense but is needed to help protect the enormous investments the bill would make in the economy,” said Michael Daniel, who served as cybersecurity coordinator to Obama.

Energy and trade

The bill’s new initiatives include $750 million over four years in Energy Department grants to help domestic manufacturers refit their factories to recycle batteries. DOE would also get another $100 million annually for four years to fund pilot projects that develop, process or recycle so-called rare earth minerals — elements needed for a variety of technologies including electric batteries.

The bill has funding for an Earth-mapping initiative to better understand mineral reserves as well as money to build a rare earths demonstration facility at the U.S. Geological Survey. It would also expand research at the DOE to give batteries a second life.

The entire bill puts an emphasis on buying from American companies by preventing money from going to projects unless “all of the iron, steel, manufactured products, and construction materials used in the project are produced in the United States.” It also includes the “Make PPE in America Act,” which would require the government to stock up on personal protective equipment for pandemics from domestic suppliers, unless it finds that materials are not available in the U.S.

The legislation would also direct the departments of Energy and State to conduct a study on forced labor in China involved in the electric vehicle supply chain.

Agriculture

The deal pours billions of dollars into Agriculture Department programs aimed at preventing natural disasters like wildfires and floods that have slammed farmers, ranchers and rural communities in recent years. The legislation calls for $3.3 billion for USDA and the Interior Department to manage forests and reduce the risk of fires. The proposal would also remove a $30 million cap on the Reforestation Trust Fund with a goal of planting 1.2 billion trees across national forests over the next decade.

The bill also creates a $2 million pilot program for USDA to partner with academic institutions to study the cost and environmental benefits of using agricultural bioproducts in construction. For example, mass timber — an increasingly popular building material made from compressed layers of wood — is seen as a more climate-friendly alternative to steel and concrete.

Waterways and ports

The infrastructure bill would boost funding for waterways and port upgrades, making about $17 billion available across a variety of programs. That includes about $1.5 billion for the Army Corps of Engineers to use on upgrades to river and harbor infrastructure.

Sam Mintz, John Hendel, Alexandra S. Levine, Sam Sabin, Eric Geller, Ryan McCrimmon, Gavin Bade, Rachel Roubein and Sarah Owermohle contributed to this report.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO