Opinion | What the White House Doesn’t Get About Disinformation

The Biden administration recently escalated its campaign against the death-bringing Covid misinformation that’s propagated on social media and on cable news and advanced by Republican scaremongers.

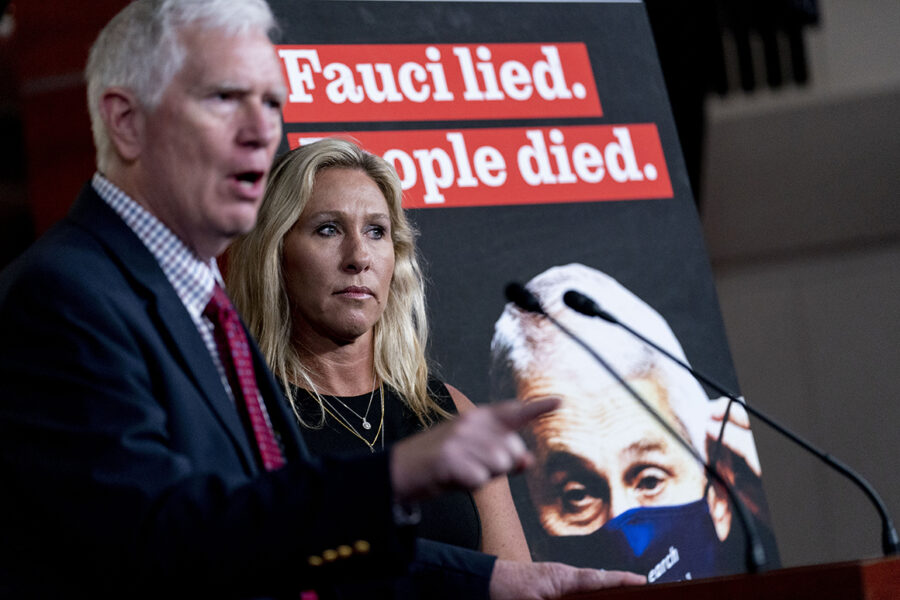

Abandoning its previous, more passive strategy, the administration has wrapped its critics in a clinch and commenced counterpunching. White House press secretary Jen Psaki lectured Facebook this week for allowing false claims about Covid and vaccines to run wild on the service and announced that the White House was “flagging problematic posts” for the company’s attention. Last Sunday, chief medical adviser Anthony Fauci hat-tricked the misinformation topic by appearing on ABC’s This Week, CNN’s State of the Union, and CBS’s Face the Nation to mute the conspiracy theory popular at Fox News and on Twitter that Biden intends to send federal agents door-to-door to forcibly dose Americans. Psaki did some of the same by lighting into Georgia Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene’s Covid fantasies while the White House Covid coordinator grappled with the Missouri governor on the other side of the ring and the surgeon general described Covid misinformation as “a serious threat to public health.”

But Biden outdid his aides with this Friday statement about Facebook. “They’re killing people,” the president said.

It’s despair-making that misinformation about Covid and other topics takes root so easily and demands constant monitoring and refutation. Misinformation—false and fake stories—has always been with us, but it didn’t really begin to flood our political debates until the 2016 presidential campaign, as Donald Trump used it on social media and TV appearances as his prime political strategy. Trump’s exile from Facebook and Twitter has tempered but not tamed the production and consumption of misinformation as his inheritors have taken up some of his slack to subvert and confuse.

The new White House strategy of directing Facebook to put a crimp on misinformers might prompt a few spectacular headlines. It might persuade Facebook to throttle Covid misinformation. It might earn a few attaboys from public health types. But so far, the effort seems to be backfiring, especially among conservatives and social media users who have criticized the government for censoring Covid- and vaccine-related information it opposes.

There’s no precedent in the Internet era of the U.S. government forcibly shoving back into the bottle an idea that has escaped, so Psaki and the White House would be wise to recall their campaign and rely more on what several recent academic studies have taught us about battling misinformation. Evidence exists that suggests we can manage misinformation without resorting to direct censorship by encouraging social media users to be more mindful of accuracy when posting.

No critique of misinformation is complete without a passage detailing how journalists have, at times, been the greatest purveyors of the stuff. Reporters—and not just the ones from supermarket tabloids—have faked stories and deliberately hoodwinked readers with hoaxes. They have advanced as news various whispering campaigns alleging unproven malfeasance and conspiracies by presidents, corporate leaders and celebrities. At the turn of the last century, yellow journalism’s excesses contaminated our media. As Brent Staples just wrote in the New York Times, until recent decades, American newspapers routinely ran scurrilous fake news about Black people, depicting them as subhuman, congenitally criminal, rapists and dope fiends. And it wasn’t just Southern papers, Staples points out, but nearly every newspaper. The coverage of Black people was as dishonest and corrupt as any modern-day misinformation campaign, and it took multiple generations to reform. The hundred-year campaign against marijuana provides another example of the press peddling misinformation.

Traditionally, the mainstream press worked with the government, industry, labor and other leading institutions as an agent of social control, using shame, restraint and persuasion to advance a national political consensus. This gateway function began to falter in the 1960s when thinkers like Rachel Carson, Betty Friedan, Ralph Nader, Martin Luther King Jr., Jane Jacobs, the Vietnam War critics and others attacked and eroded the consensus. Dynamiting the consensus machine was a great thing, but there was an unwanted side-effect. The forces that blocked inconvenient truths had also helped control the spread of nutbaggery. As the Web and social media knocked down the gatekeepers, more inconvenient truths gained currency. But so too did the nutbaggery.

For example, in pre-Web years, believers in the tenets of the John Birch Society had no idea of how many people agreed with them that President Dwight Eisenhower was an agent of the international communist conspiracy. They existed in a state of “pluralistic ignorance,” which inhibited them from fully voicing their opinions. But the Web shattered this ignorance, encouraging their modern-day equivalents, QAnon believers, to unite and circulate their misinformation. Anti-vaxxers like Robert Kennedy Jr., and broadcaster Tucker Carlson would have never gotten a chance to churn their fetid wake of lies and deceptions about Covid in the days before the Web and cable news.

The most sobering thing about the misinformation of our age is how fast and how far it moves compared to earlier years. A 2018 MIT study shows that fake and false news (characterized as such by six well-known fact-checking organizations) spreads faster on Twitter than true stories, it’s retweeted more often, and it spreads farther. Fake news is 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than real news and people, not bots, are doing the primary spreading. The MIT researchers—Soroush Vosoughi, Sinan Aral and Deb Roy—attribute fake news’ superspreading powers to the novelty and excitement that sharing hogwash brings. Nobody gets—or expects to get—a jolt from sharing a news story about community organizers who are sharing pointers about where residents can get vaccinated. But the vision of G-man thugs force-injecting you on the front porch, espoused this week by Marjorie Taylor Greene in a tweet? That’s enough to stimulate fight-or-flight in anybody. (She got 11,525 replies to that tweet, 5,852 retweets, and 14,826 likes.)

What’s the appeal of tweeting misinformation? “People who share novel information are seen as being in the know,” Aral told Science magazine, and who doesn’t like to be thought of as ahead of the curve? “People respond to false news more with surprise and disgust,” Vosoughi says, while true news elicits sadness, anticipation and trust. The appeal of the bogus is so grand that a BuzzFeed News investigation found that in the last three months of the 2016 presidential campaign, “the top-performing fake election news stories on Facebook generated more engagement than the top stories from major news outlets such as the New York Times, Washington Post, Huffington Post, NBC News, and others.”

A March study published in Nature explains that most social media users don’t deliberately set out to share fake news. The researchers contacted more than 5,000 Twitters users who had shared links to two right-wing sites rated by fact-checkers as unreliable. They made no effort to correct the tweeters’ tweet but instead asked their opinion about the accuracy of an unrelated, non-political headline. The researchers didn’t expect an answer; they merely wanted to remind the respondents that accuracy mattered. This single subtle reminder appears to have increased the “quality” of the news that they later shared. “People are often distracted from considering the accuracy of the content,” researchers David Rand and Gordon Pennycook wrote. “Therefore, shifting attention to the concept of accuracy can cause people to improve the quality of the news that they share.” It would be great if everybody consulted a cheat sheet of misinformation to avoid before tweeting, but that’s not the case. Another group of researchers found that fact-checker takedowns of false articles almost never reach the people who share the false articles.

The good news is that over 80 percent of respondents in the Nature study said it was important to share accurate information on social media. Also, the respondents were actually shrewd about separating true from false accounts when they put their minds to it; when people share false accounts, the researchers found, it’s often due to not paying adequate attention before clicking send. Who falls the hardest for fake news? People who are “more willing to overclaim knowledge,” Rand and Pennycook write elsewhere.

When a user shares something, it doesn’t necessarily mean he believes it, Rand and Pennycook note. It seems that he’s mostly trying to impress his followers and entertain them. Social media is, of course, optimized for engagement, not truth, and the impulse to be the first to tweet or retweet an item prevents many users from judging its accuracy beforehand. These findings counter the common view that we’ve entered a “post-truth” vortex in which people don’t care whether something is true or not. Most people do care, but tweet garbage anyway. Many of us have been known to commit this sin. Raise your hand if you’ve ever tweeted a bit of fakery that you shouldn’t have.

If people are sincere about wanting to share accurate information—and if nudging them toward accuracy puts them on a course to share more quality information—we might be inspired to think that the struggle against misinformation isn’t hopeless. Both Twitter and Facebook now label and suppress what they consider to be misleading messages, actually booting Trump from their services. But the labeling has only met with a modicum of success. One unintended consequence of warning labels is that some users have come to interpret messages without labels as endorsed as true by the social media outlet. Sometimes you can’t win for losing.

Instead of jawboning Facebook or accusing it of murder, the White House could consider asking, not commanding, social media companies to prod users into thinking before posting. Whatever strategies the White House ends up promoting to marginalize fake news—banning, “prebunking,” suspending, blocking, labeling, nudging, tweaking the algorithms—we’ve got to accept that there will always be a contingent who delight in writing, reading and sharing blatantly untrue material. To varying degrees, we all seem to be as attracted to the outrageously false as we are disappointed by the dullness and predictability of the true. Our psyches tend to burn brighter when stoked with the fantastic and astonishing. This can pose an insurmountable problem for reality-based journalists who learn how difficult it can be to compete with the fake stuff. Back in the 1920s and 1930s, a slang term arose to describe this kind of thinking. It was called “thobbery,” and was defined as the confident reasoning of a person who is not curious about verifying his results.

It will always take mental energy to stand up against the fake and the spurious, and nobody will ever devise a magic formula to extinguish misinformation. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t think before we retweet, and ask our family, friends and neighbors to do the same. The best guideline would seem to be this: If you stumble across an incendiary tweet that could easily be translated into a Day-Glo circus poster, leave it alone. Thobbery is for chumps.

******

Why is there so little fake sports news? Is it because sports fans are knowledgeable about the subject and ignore hype? Send your speculations to [email protected]. My email alerts are all about misinfo. My Twitter feed tweets only the fake. My RSS feed disdains social media.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO